More often than not, women are overshadowed in the art world. And while…

What is modern Arab art?

What is modern Arab art?

Modern Arab art (al-fann al-’arabi al-hadith) can be defined as art production of the Arab region, or of those who consider themselves ‘Arab’, executed in the Western modality. This art form first appeared in the region at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Inspired by Western forms of creation, art in this modality at first led to the abandoning of the traditional art practices such as Islamic art in the region. The existing scholarship has identified three phases of modern Arab art: adoption, adaption and globalisation.

The first phase, the so-called adoption of Western art, occurred at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of 20th century. During this phase the indigenous regional art practices were eventually abandoned as art in the Western modality, for instance easel painting, became increasingly popular. This phase is closely related to the prevailing cultural idea that Islamic art was essentially a non-art since it did not satisfy the naturalistic criteria attached to the art movements dominating in Europe. As a result, Islamic art was rejected since it was not figurative or mimetic – the prevalent ideals in Western art at the time. Consequently, the absence of ‘real’ art in West Asia and North Africa was taken as a sign of cultural backwardness, while the ability to adopt Western art was seen as a ‘proof’ that Arabs could adapt to modern civilisation.

In many countries in the region this first phase was partially a top down initiative, driven by states or members of the modernising elites. As countries wanted to ‘catch up’ with Western art, fine art schools modelled on the Parisian example were created throughout the region. One can think of the Fine Arts Schools in Istanbul (1883) or in Cairo (1908), where Prince Yusuf Kamal, an active early art patron, financed the school during its first years. Lebanon, Syria and Iraq followed this trend slightly later.

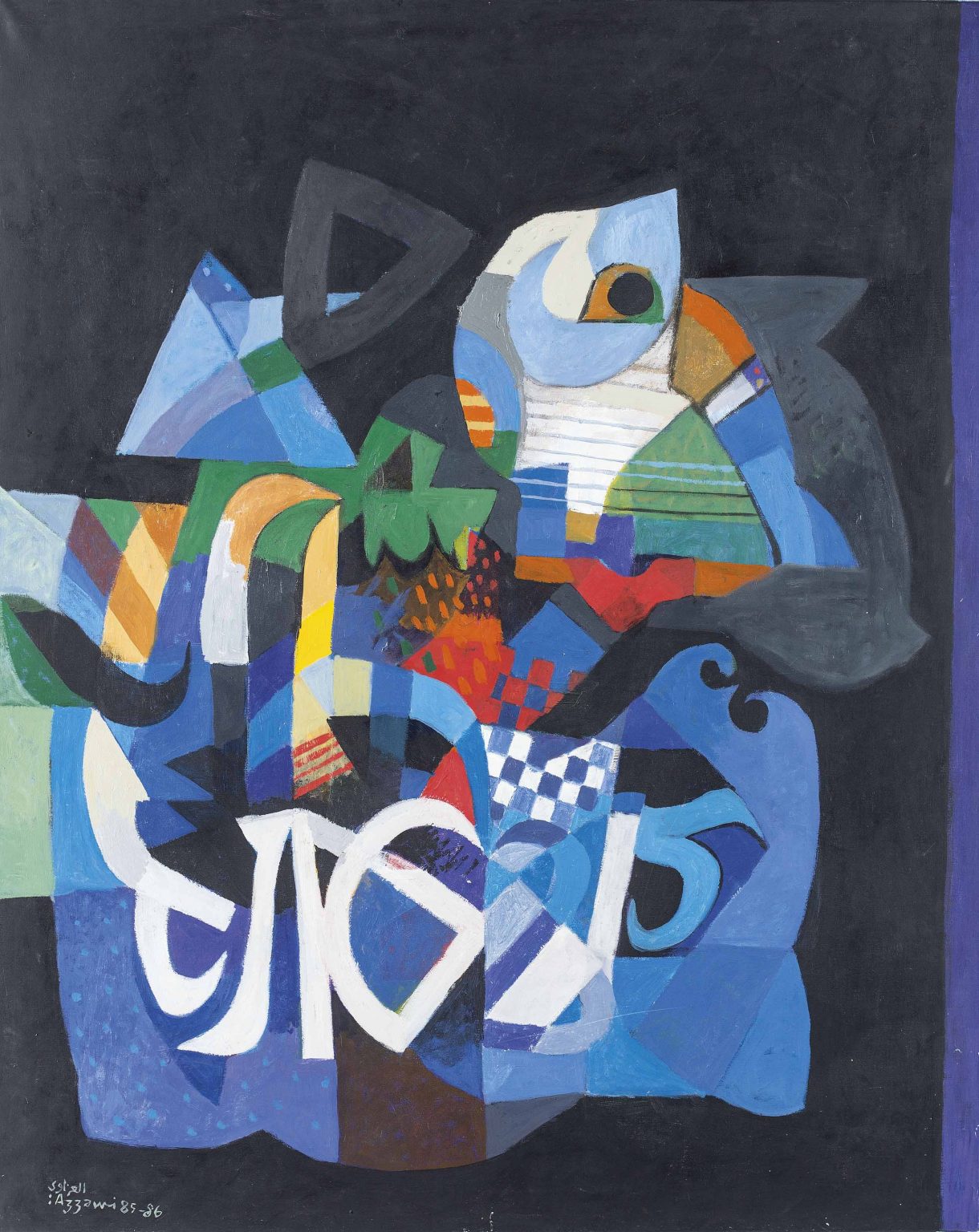

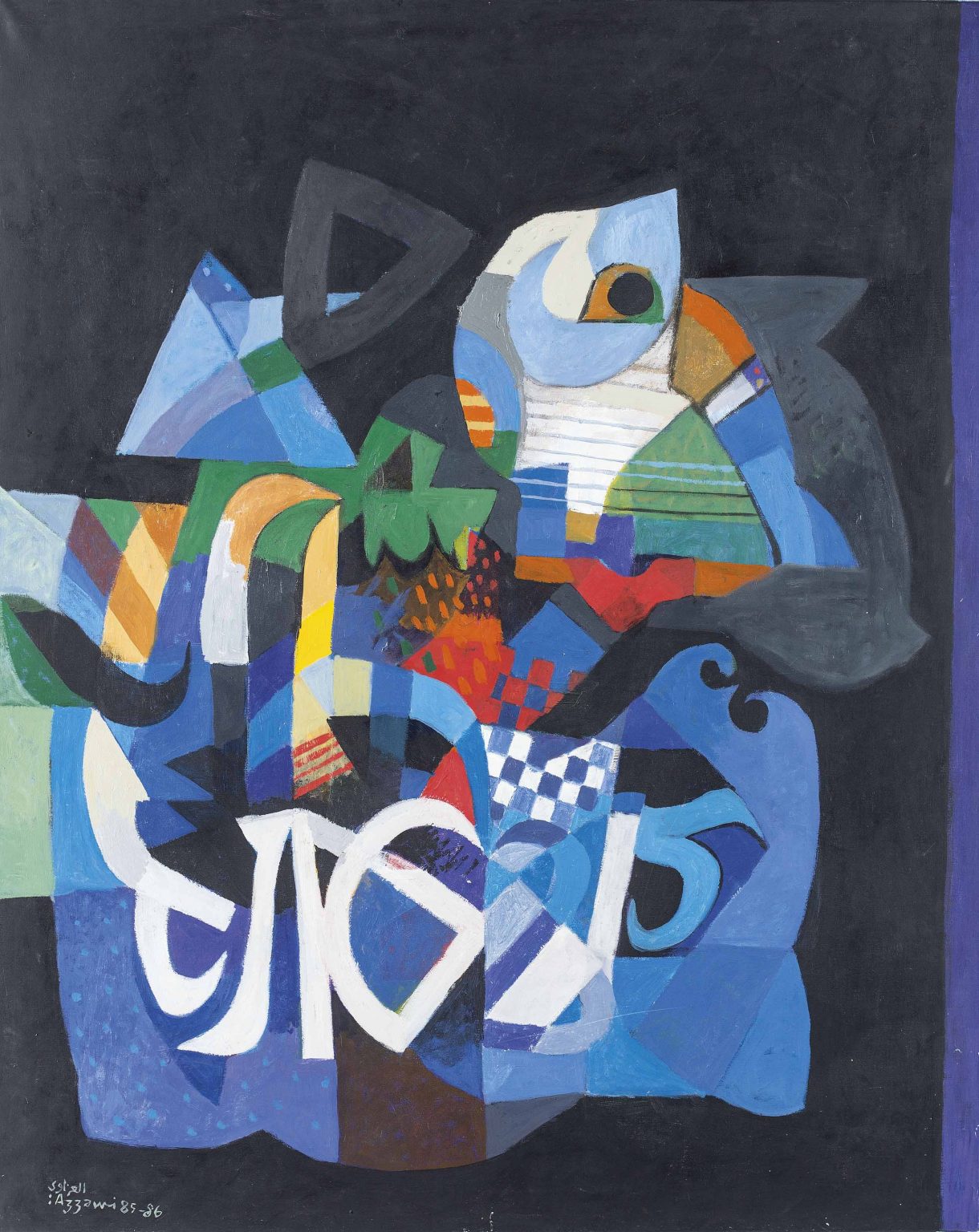

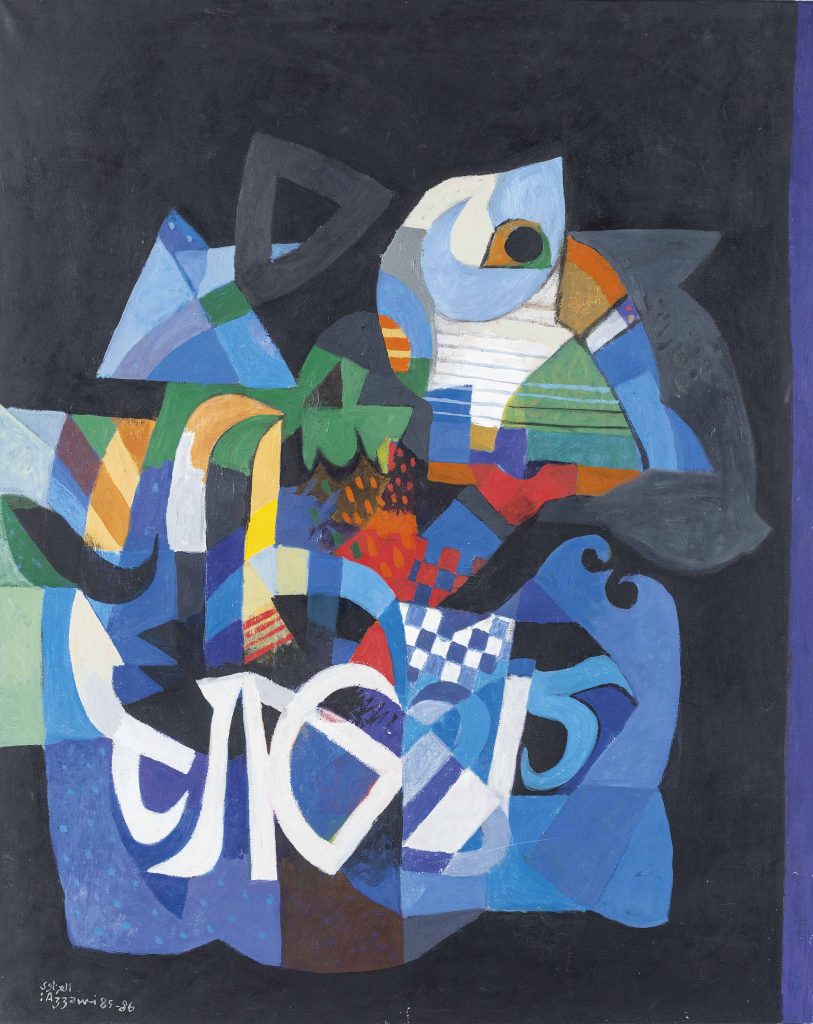

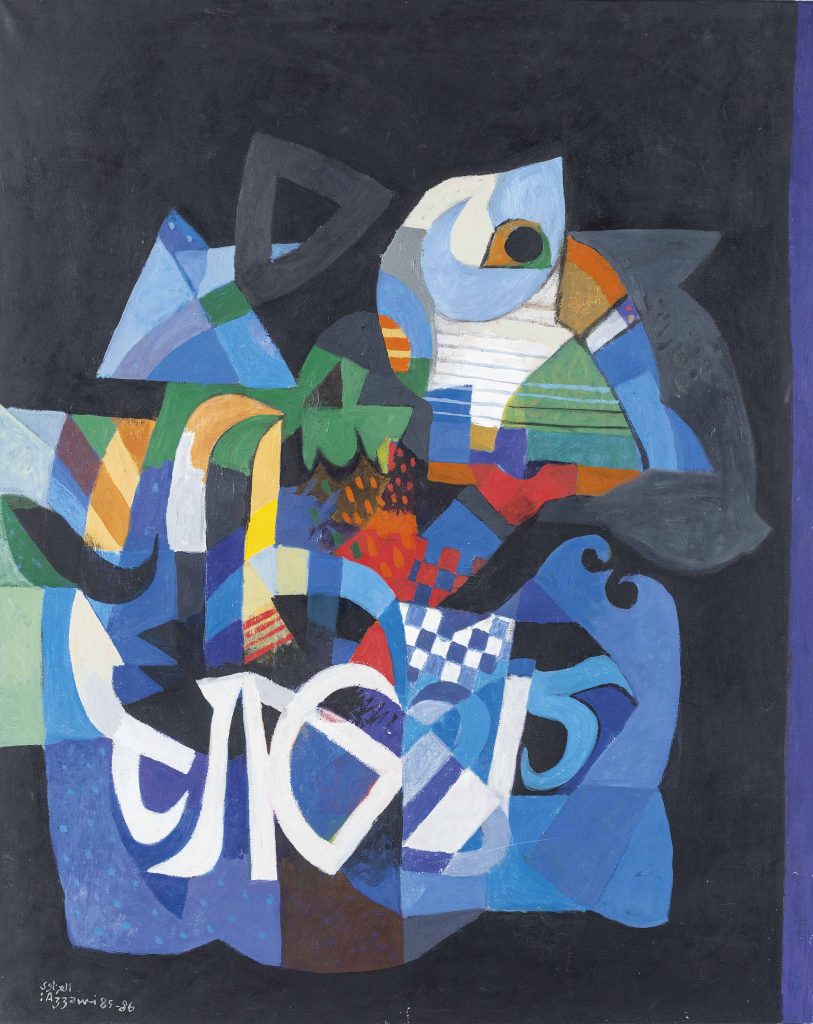

The first phase was followed by a period of adaptation in the post-independence period of the 1950s. This second phase was characterised by the rediscovery of the local and re-appropriation of the arts of older civilisations that had influenced the region, including but not limited to Islamic ones. The older cultural influences including various traditions and motifs were adapted to the earlier adopted Western art typology. Whilst the earlier phase was occupied with ‘catching up’ with the West, in the second period artists were concerned with finding authenticity (asāla).

The second phase which started around the 1950s and to an extent ended in the 1990s was closely related to two important factors: most Arab states gained independence during this period, and the discovery of the numerous revolutions that Western art had undergone since the turn of the century. With independence came the will to develop indigenous, authentic culture. Together with Arab nationalism, artists and intellectuals were increasingly interested in various forms of local cultural expression. It was about time to return to ‘Arab roots’, as many articulated. Artists focused their efforts in integrating and translating local traditions in the earlier adopted Western art.

The third phase, the so-called globalisation period started in the 1990s. During this phase a part of the art production of the Arab world has become part of the international art scene. This globalisation is visible in other non-Western modernities, too, as it intensified with the opening of Centre Pompidou’s Magiciens de la terre exhibition (1989). In this exhibition non-Western artists were exhibited for the first time as part of the international art scene in a prestigious Western institution. Particularly after the 9/11 the Western art world became increasingly interested in contemporary art of the region. This trend has resulted in numerous exhibitions including MoMA’s Without Boundary, Seventeen Ways of Looking (2007), Saatchi’s Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East (2009) and New Museum’s Here and Elsewhere (2014), demonstrating how contemporary art from the region interests, whilst modern art remains far less popular, if measured in terms of exhibitions.