L’Apocalypse Arabe

L’Apocalypse Arabe

Etel Adnan is a visual artist, essayist, and poet whose multicultural and distinct work embodies a dichotomy that is universally realized in its stance against the notions of universalism itself. Born in 1925 in French mandated Beirut to a Muslim Syrian-Ottoman father and Christian Greek-Ottoman mother. By the age of 5, Adnan acquired both Turkish and Greek from her parents and then later acquired French due to the French mandated colonial system in Lebanon that operated against any formal education of the Arabic language. Arabic then assumed an ominous yet ever prevailing presence in both her work as well as her life. In her own words, “The Arabic language has a certain aura for me, partly because we were forbidden to learn it in the French schools and we were punished if we even spoke it. And because we spoke it neither at school nor at home, I was locked out of it. I speak it in the street but can’t write a poem in Arabic. This means I’ve made Arabic into a myth, into a kind of lost paradise”. Her definition of language evokes something of the tragedy of Babel. In biblical literature, God punishes the people of Babel by confusing them with diverse languages, disabling them from communicating and ultimately nullifying their attempt to construct a tower that would have led them to the heavens. Language, to many born into a dynamic of internal exile, can be rendered as disabling, or even violent at times.

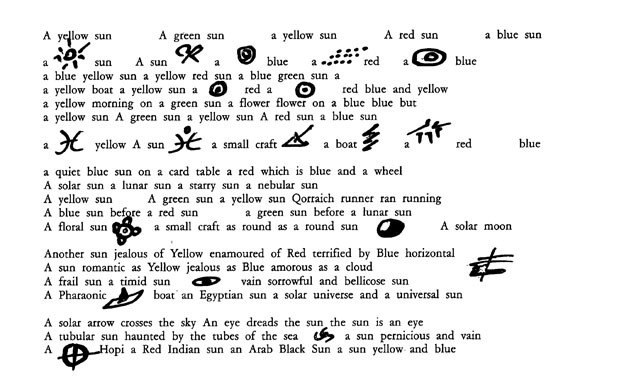

Her genre-defying, book-long poem L’Apocalypse Arabe (1980) was first written in French (later published in English and Arabic) in the context of the tragedy that surrounded the events of Lebanon’s devastating 15-years long civil war. But initially, it started on the basis of an “abstract poem on the sun” which forcefully assumed figurative relevance in the civil war of 1975. The author explains the shift by saying “the war took it over. I don’t know what it [the poem] would have been if the war hadn’t happened”. Although the author wrote this during a specific period of socio-political turmoil in Beirut, the work also addresses issues surrounding the global struggle endured by colonized people in their pursuit towards national liberation. Her anti-colonial stance was also accentuated in her 1973 book “Beirut-Hell Express” where she wrote “Take your vertebrae and squeeze out / colonialism like pus”. We thus find in her work a deception of tragedy that echoes beyond the Lebanese struggle, whilst also offering a critique of colonialism and oppression in all its variants. Adnan’s commitment as a diverse visual artist intermingled with her political commitments. Within her corollary of visuals and text, the sun in the Arab Apocalypse stands as an overlooking, everlasting witness to the struggle not only of Arab people but of all subjugated people.

The events then urged her to write about her unique experience as someone from within but also without. Although the focus is placed on the tragedy to befall Arab nations, it also operates as a work of postcolonial resistance because of its inclusion of cultures distant from the region, diluting the narrow definitions of national identity (of which language is pillar) and constructed loyalties. This testimony, assimilated in The Arab Apocalypse in the form of prose that is assembled at length, distributed in lines, and disrupted by micro illustrations of swirls, suns, eyes, waves, amongst other allusive symbolism. This expresses sentiments that are lost within the narrow confinements of language and communication. The Arab Apocalypse is proportionally visual as it is textual. It operates as a work that provides an alternative to typical textual expression, “as if the verbal language alone had become an inadequate means of self-expression to Adnan”. Viewing The Arab Apocalypse as distinctly a poem, a book, a work of postcolonial resistance or even just as an eyewitness account, would confine it into a singular limited narrative. Instead, the reader must step back and look at the environment surrounding the text and visuals encrypted in The Arab Apocalypse. Only then they will realize that the book, in the words of Aditi, “Attend(s) questions of representation in literatures of witness. In so doing, the text becomes a disaster in the process of witnessing disaster.”

Authors, more than just mere prescribers of situations, are also subject to being complicity involved in events and struggles. Between the objective aim of storytelling and the personal subjective role that drives a writer to prescribe events, lies a lost world composed of feelings and expression. Adnan’s positioning between various different cultural, religious, and linguistic worlds are articulated amidst words and visuals and relate to a sense of confusion brought about politically induced cultural amnesia. An illusion we can no longer distance ourselves from in the reality of today’s hybridised, or rather globalised artistic spaces.

References:

Aditi Machado (2016) On Etel Adnan’s ‘The Arab Apocalypse’, Available at: https://jacket2.org/article/etel-adnans-arab-apocalypse#n4 (Accessed: 10 February 2021 ).

Majaj, L.S. and Amireh, A. eds., 2015. Etel Adnan: Critical essays on the Arab-American writer and artist. McFarland.

Obrist, H.U., 2014. Conversations with Etel Adnan. Etel Adnan in All Her Dimensions, pp.28-95.

Sonja Mejcher-Atassi, “Breaking the Silence. Etel Adnan’s `Sitt Marie Rose and The Arab Apocalypse,” in Poetry’s Voice – 35 Society’s Norms, Forms of Interaction between Middle Eastern Writers and Their Societies, dedicated to Angelika Neuwirth, eds.

Recommend reading :

ايتل عدنان كاتبة عربية.. بلغة أجنبية – صلاح سليمان

L’Apocalypse Arabe

L’Apocalypse Arabe