First Museums in WANA

First Museums in WANA

Have you ever wondered about the history of museums in West Asia and North Africa? When were the region’s first museums established? What kind of museums were they? Whilst there were both ancient and medieval museum prototypes in the region, museums in our current understanding of the term were introduced in the second half of the 19th century to the region. (If you are interested in learning more about the earlier ‘museums’ or, say, museum predecessors, I recommend you to take a look at this brilliant piece by Dr Pamela Erskine-Loftus.)

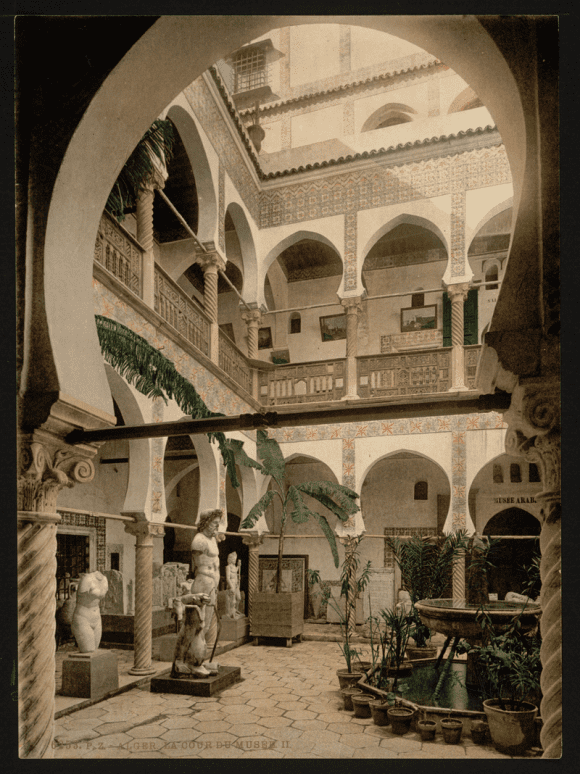

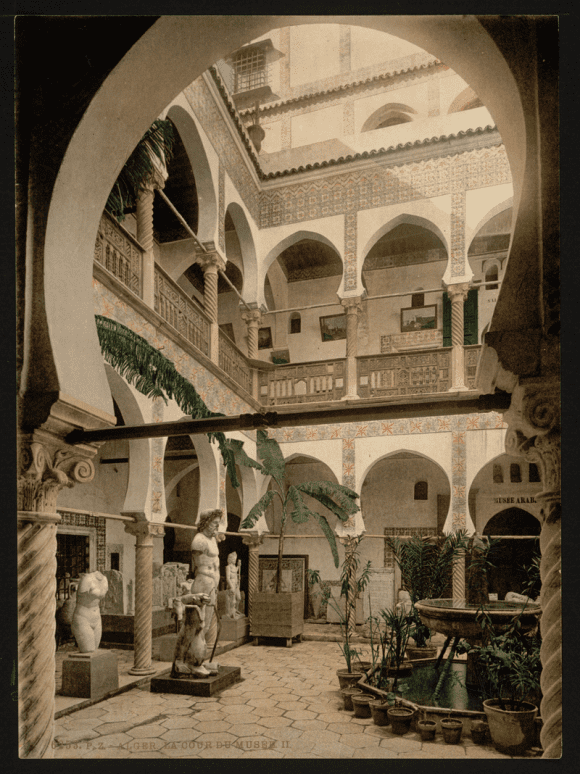

All the early museums in the region were archaeological. Consider, for instance, the Armaments Museum in Istanbul (1846), the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (1858), the Archaeological Museum of the Syrian Protestant College, which later became the American University of Beirut (1868), or the Bardo National Museum in Tunis (1888). Other examples include the Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria (1892), the National Museum of Antiquities and Islamic Art in Algiers (1897) and the Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Archaeology Museum in Jerusalem (1902).

These early archaeological museums were very similar to their Western counterparts. In fact, they shared the same Western museological values and principles such as classification and taxonomy, the two ultimate ideals guiding the Western museological practice since the Enlightenment, as they collected and exhibited objects and artefacts from the ancient past.

Here, it is crucial to underline that the very priority given to the archaeological past is inherently Western. At the time it was fashionable to believe that the ancient civilisations are superior to the present moment. This continuous, and to a great extent systematic preference of the ancient over the modern is still visible both in the West and in the WANA region. In WANA, one of the most striking examples of this priority granted to the archaeological memory concerns the difference between the archaeological-historical museums and modern art ones: the latter are barely visible, whilst the first rather celebrated across the region.

As the creation of the early archaeological museums took place during colonial rule and since most of these institutions were mirrored on the Western examples, these museums are essentially products of colonialism. In fact, it would not really be an overstatement to say that it was colonialism that brought the idea of the museum to the region. Whilst the actual involvement of Western professionals differed from an institution being entirely created and managed by Westerners to the aid being more indirect of nature, the early museums rarely, if ever, adopted themselves to the local particularities.

The prevailing knowledge system was strongly anchored to the Western academia, producing essentially Western readings of history, thereby ignoring the local understanding and creating a potentially sharp contrast between the museum and the ‘reality’. Many museologists and anthropologists have critiqued the colonial museum for its static and potentially harmful position. The Angolan writer and anthropologist Henrique Abranches, for instance, famously called the colonial museum a warehouse emphasising how the displayed objects and artefacts were separated from the people who had created them. The most fundamental critique towards the colonial antiquity museums, however, stems from the way the West exerted authority through these objects. Although the local population was shown objects and artefacts from their past, the presentation of the collection through the museum emphasised their peripheral position vis-à-vis the West.

The so-called second wave of museums in the region took place closer to the mid-20th century. The Western influence on the museological practices and the very understanding of ‘museum’ did not really decrease, as most of these newly established archaeological-historical-national museums continued to adhere to the earlier articulated Western vision of history. In practice, the ancient, pre-Islamict heritage was integrated into the new nationalisms as this period witnessed the establishment of several national museums, including the Syria National Museum in Damascus (1919), the Iraqi Museum in Baghdad (1926) and the Jordan Archaeological Museum in Amman (1951).

Does the history of museums really matter nowadays, someone might ask. Well, should you not enjoy museum visits in the region because of the somewhat complicated history with Western ideals – absolutely not. The museums in the region are there for our enjoyment, education, pleasure, reflection – and everything else you might gain from them. But should there ever be a situation, where it is implied that the history of museums is somehow a neutral topic, natural progression or that the archaeological memory and the ancient past should take priority over the modern or contemporary one – then it becomes absolutely crucial to reflect on the history of the region’s museums and be mindful of the fact how strongly we can still feel some of the centuries old, perhaps long outdated museological ideals and values.

Image: the National Museum of Antiquities and Islamic Art (Algiers).

You might also like:

First Museums in WANA

First Museums in WANA