Implications of the “Contemporary Art from the Islamic World” (1989) Exhibition

Implications of the “Contemporary Art from the Islamic World” (1989) Exhibition

The history of the global contemporary art era conventionally begins with the 1989 Centre Pompidou exhibition, Magiciens de la terre, which presented non-Western art as art rather than as an object of ethnological curiosity for the first time at a prestigious Western art institution. Five of the around hundred artists came from an Islamic background: Rasheed Araeen (Pakistani living in London), Shirazeh Houshiary (London-based Iranian), Sarkis (Armenian from Turkey living in Paris), Yousuf Thannoon (Iraqi calligrapher) and Boujemaa Lakhdar (Moroccan artist). In the conventional narrative the Centre Pompidou exhibition inaugurated a new era in which artists from non-Western backgrounds slowly became part of the international (read ‘Western’) art world system. What is, unfortunately, lacking from this narrative is an exhibition dedicated solely to artists from the Islamic lands, also organised in 1989 at a prestigious Western institution: Contemporary Art from the Islamic World at London’s Barbican Centre. In this article, I am not so concerned with the reasons why this aforementioned exhibition is occulted from the canon, although there is certainly plenty of room for speculation, but the relationship between this exhibition and art from West Asia and North Africa.

Here’s a backstory to the exhibition: put together by Wijdan Ali, the founder and driving force behind the Amman-based Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts (JNGFA), the exhibition was the Gallery’s first group show outside of Amman presenting an entire region. Since its establishment in 1980, the museum had organised exhibitions outside of Jordan, for instance Jordanian Contemporary Art (1983) in Ankara and, similarly, in Poland (1984) and France (1986), but the Contemporary Art from the Islamic World was the institution’s first large scale group show abroad. The exhibition presented a number of artists from the Islamic world including Algeria, Bangladesh, Brunei Darussalam, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Malaysia, Morocco, Pakistan, Palestine, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Yemen, and UAE, KSA, Oman, Qatar, Kuwait and Bahrain grouped together as the Gulf countries. The exhibition catalogue included short essays describing each country’s or group of countries’ artistic practices to provide the visitors some historical background and context.

Before I continue discussing the exhibition and its implications further, a few words about the state of research on art production of the region during the 1980s and 1990s. While the research on contemporary and modern art hailing from West Asia and North Africa has developed quite a bit in the past years – that is not to say the field remains, still, largely unexplored – in the 1980s and 1990s the situation was quite different. The scholarship focused on the study of Islamic art, a Western discipline examining the artistic production of the Islamic world, conventionally from the 7th to the 19th centuries. The existing research on non-Western modernities, for instance modernities and modern art originating from the West Asia and North Africa, was almost non-existent as the dominating thought saw modernity as an inherently Western phenomenon: non-Western modernity was, if anything, a pale imitation of the West – not worthy of attention.

As the (Western) art historical research was painfully slowly opening to the art production of the non-Western world, several crucial developments for the encompassing study of modern and contemporary art from West Asia and North Africa took quietly place in the background. These developments include the opening of the JNGFA, one of the first museums exhibiting modern and contemporary art from across the region. There had been earlier modern art museums, for instance in Egypt and Lebanon, but these usually maintained a strong national focus in their collection policy. The approach of the JNGFA was radically different as its collection did not only focus on Jordan but instead included most of the countries in the region. Another crucial moment in this history is the JNGFA’s 1989 exhibition presenting contemporary art from the region as it reveals what kind of art history this institution attempted to create. Now, let’s not forget that in 1989 the art history of modern and contemporary Arab art was largely nonexistent in English or French, although publications in vernacular languages did exist, for instance Al’Said’s Fusul min ta’rikh al-haraka al-tashkiliyya fi-l-’Iraq (1983) and Bahnasi’s Al-fann al-hadith fi-l-bilad al-’arabiyya (1980) and Ruwwad al-fann al-hadith fi-l-bilad al-’arabiyya (1985). The role of institutions and the individuals behind them was hugely important as they could advance their agendas or views within a scarce intellectual space.

Despite the exhibition’s seemingly neutral sounding title, Contemporary Art from the Islamic World, a more careful exploration of the exhibition catalogue reveals the existence of a peculiar concept: modern Islamic art. In the introduction of the catalogue Wijdan Ali argues for the existence of modern Islamic art, rooted in the traditional art practices of the various Islamic empires. This argument holds that there is an art form specific to the Islamic world and it is based, without any interruptions, on the old traditions of the region.

So what, you may now wonder. What’s wrong with the term ‘modern Islamic art’? As the artistic creation in West Asia and North Africa changed (i.e. the adoption of easel painting) during the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, the artists of the region deliberately abandoned their indigenous, including Islamic, art practices. There were many reasons for this, one being the internationalisation of Islamic art as a non-art. As a result, art in the Western modality became increasingly popular. The physical manifestation of this period include newly established art schools, for instance Académie libanaise des beaux arts in Beirut (1937) and Ma’had al-funun al-jamila in Baghdad (1941). Art in the Western modality did not dominate the region all the time, though. In the 1950s the artists started to go back to their roots, we may speak of a so-called adaptation phase. This included drawing inspiration from the Arabic script and from older civilisations, including but not limited to Islamic ones.

Considering the aforementioned history, the use of the term ‘modern Islamic art’ becomes debatable. Ontologically, the term is inaccurate: in most of the cases there is no continuity between modern art from the region and Islamic art given the break in production modes, techniques, materials and concepts. Apart from ontological concerns, the ‘Islamic’ prefix is not defined: does it signify a cultural or a religious belonging? Similarly, the prefix, especially in an exhibition such as the 1989 one, presupposes the existence of an encompassing ‘Islamic’ visual culture at the expense of other possible denominators. What about the artist’s perspective? Did they see their work primarily as ‘Islamic’?

While the theoretical debates such as the existence of modern Islamic art can be quite fun and definitely intriguing, the implications of the 1989 exhibition and Wijdan Ali’s ‘modern Islamic art’ concept are wide-ranging and by no means merely pleasant. Whilst the JNGFA and its extremely active and early exhibition policy are to be appraised – to date, there is no such regional institution with such an impressive exhibitionary history, the popularity of the terms ‘modern Islamic art’ and ‘contemporary Islamic art’ are somewhat troubling. Indeed, these terms are often used by some powerful players in the (Western) art world, including the institutions such as the British Museum and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. These terms, when used by Western institutions with considerable imperialist and colonialist baggage become orientalising and homogenising. If these terms continued to be used, there ought to be at least a wider conversation on their history and meaning.

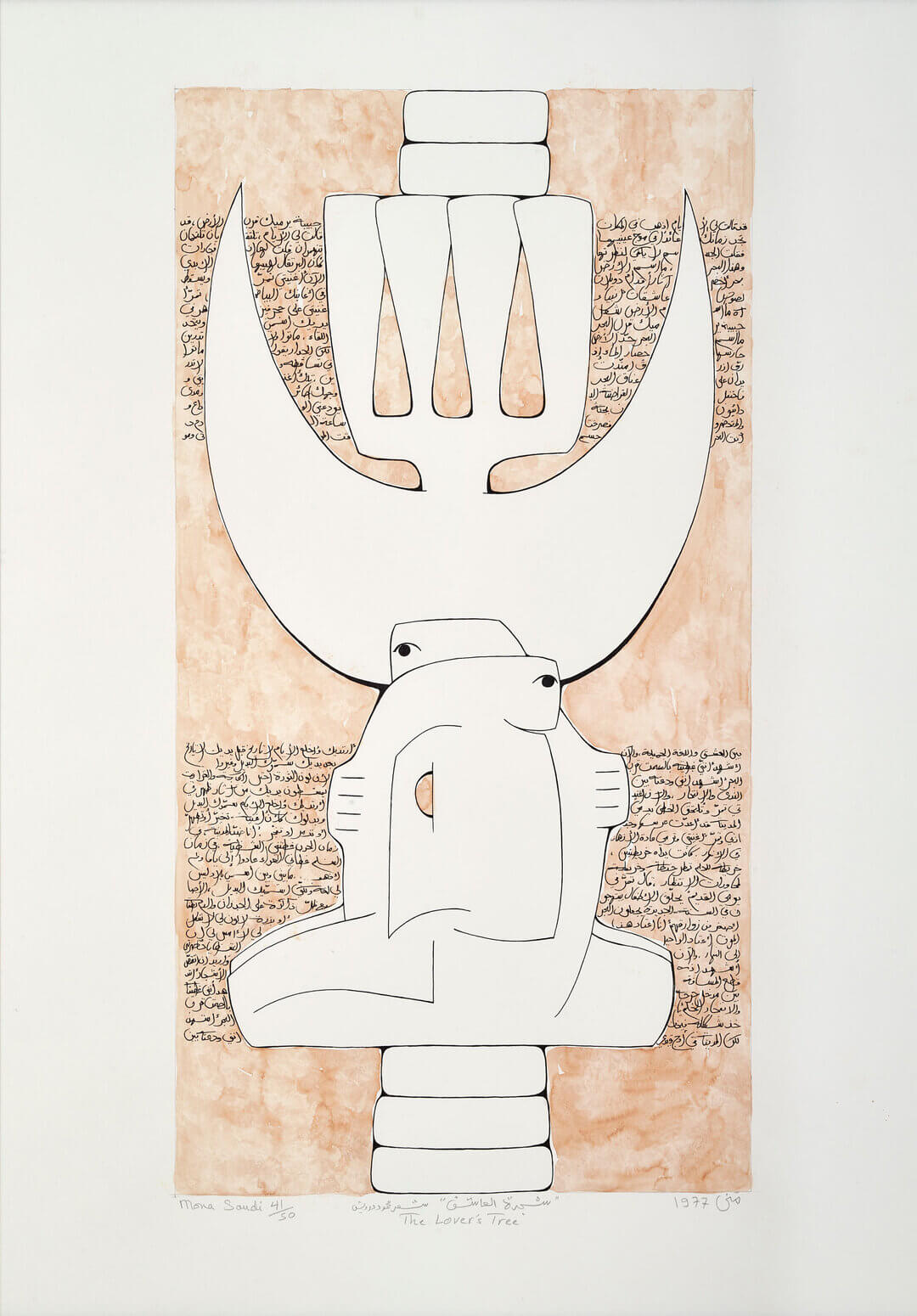

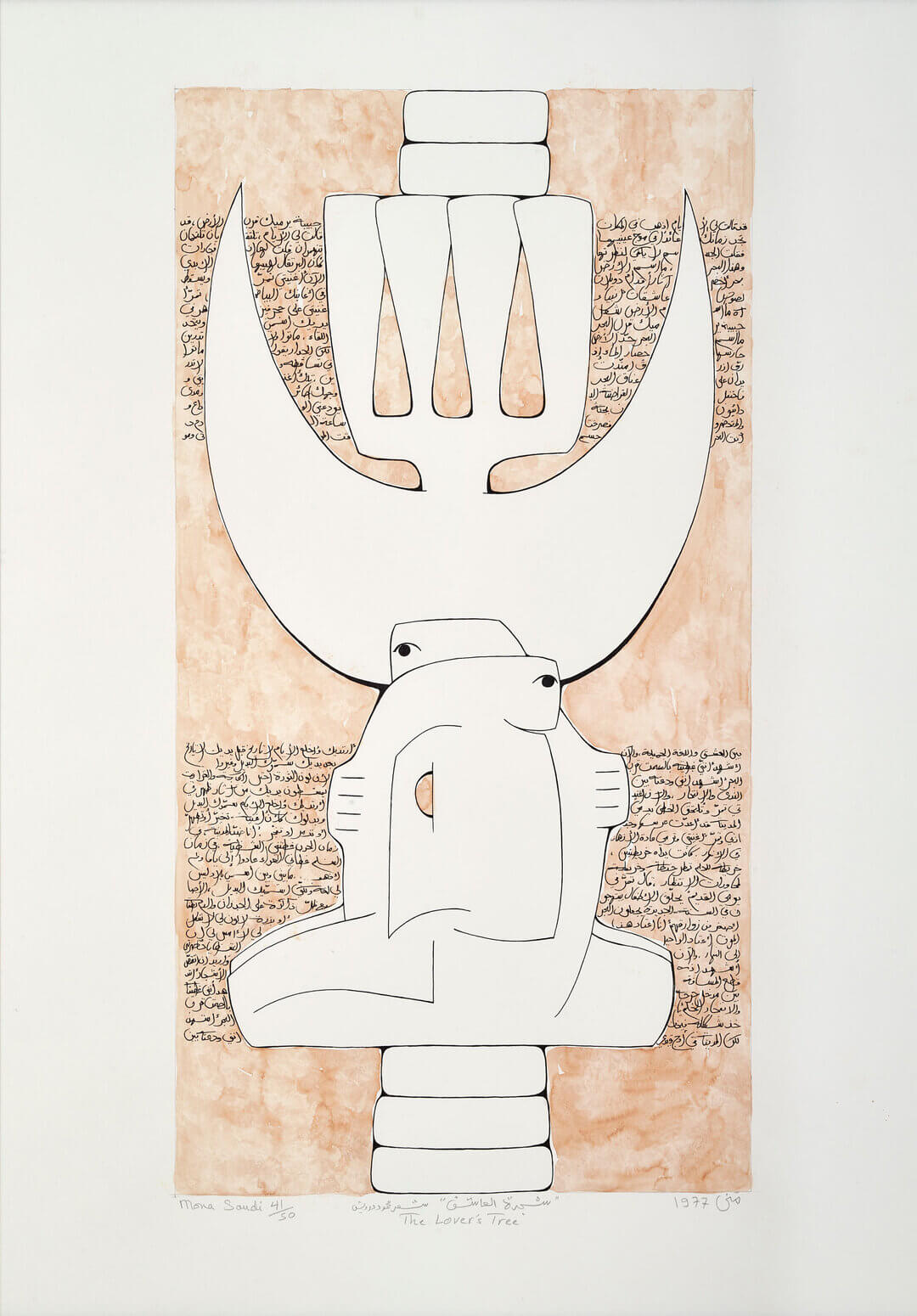

All the images in this article feature artworks from the 1989 exhibition.

Featured image: Rabab Nimer, ‘Untitled’, 1987. Courtesy of the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts.

Implications of the “Contemporary Art from the Islamic World” (1989) Exhibition

Implications of the “Contemporary Art from the Islamic World” (1989) Exhibition