test test infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical infoauthor biographical info

The Salon d’Automne and Sursock Museum

The Salon d’Automne and Sursock Museum

Date: 05 Oct 2023

By

Rana

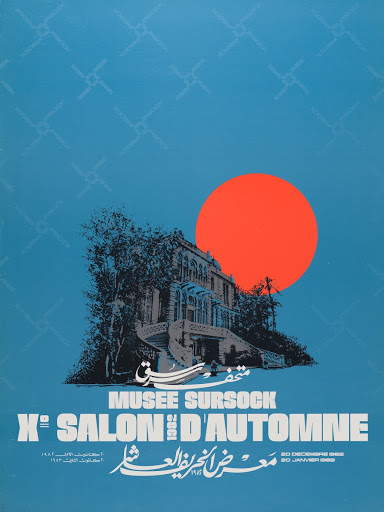

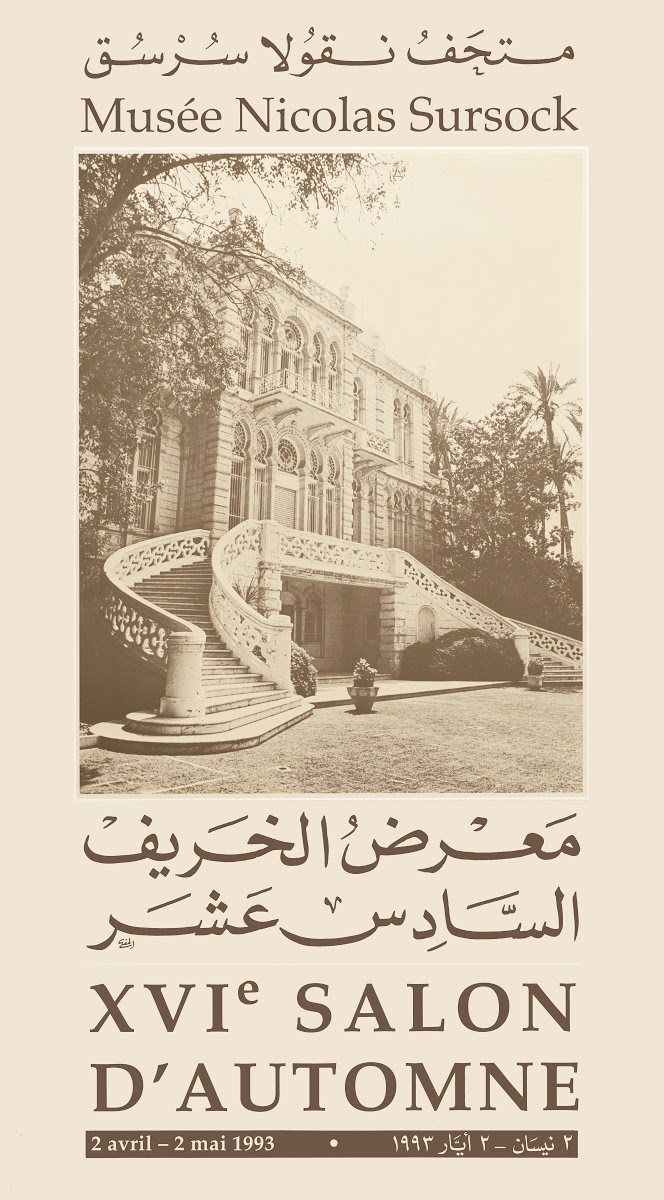

Beirut’s Sursock Museum has played a crucial role in the history of Lebanese art. Historically, there have been only few modern and contemporary art museums in the region, making the exhibitionary activities of the existing art museums even more important. Furthermore, to date, Lebanon does not have a public modern and contemporary art museum, enabling private ventures to play even more significant roles. The Sursock Museum in Beirut’s Achrafieh neighbourhood became particularly well-known for its annual Salon d’Automne, autumn salon, a group exhibition of contemporary art in Lebanon.

The Sursock Museum was created by Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock (c. 1875-1952), a wealthy Lebanese collector, who bequeathed his mansion and art collection to the city of Beirut on the condition that his villa would be turned into an art museum. Although the museum’s initial collection was not particularly focused on modern and contemporary art, but included a variety of different collections including Sursock’s personal collection of furniture, eventually the museum became dedicated to modern and contemporary Lebanese and regional art.

The museum was inaugurated nine years after Sursock’s death in 1961 with its first Salon d’Automne exhibition from 18 to 28 November. The 1960s were an exciting time for contemporary art in Lebanon, and the Salon was launched at a particularly active period: Beirut was bursting with new galleries and the city was about to establish itself as a regional art hub. Although the Salon d’Automne came to play a crucial role in Lebanese art history, by no means it was historically unique. In fact, already in 1954, the Ministry of National Education and Fine Arts had launched a Salon d’Automne to exhibit Lebanese contemporary artists. The Ministry went on to also launch a spring salon titled Salon du Printemps, and at some point, the autumn salon discontinued and the Salon du Printemps was favoured. Considering this history, it can be argued that the Sursock Museum actually continued the tradition the ministry had established. The very history of the Salon as an institution, however, is much older as it goes back to 17th century France and Louis XIV, who in 1667 sponsored an exhibition of the works of the members of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which was hung in the Salon d’Apollon of the Louvre Palace in Paris. After 1737 the Salon became an annual event, where artists could exhibit their work, and during the 19th century, the event with its various iterations and counter-salons came to dominate the art world.

The Salon d’Automne organised by the Sursock Museum was established to exhibit the works of Lebanese artists and thereby institutionalise contemporary artistic production in Lebanon. The annual exhibition also took on a significant role in guiding both artists and visitors. It could be argued that to an extent the Salon was able to establish itself as such a powerful player because of the absence of any public art museums in Lebanon. Historically, public art museums have tackled the complex and problematic notion of educating the public – often for the benefit of the nation-state and its dominating ideology.

Each iteration of the Beiruti Salon consisted of a Jury, which in the beginning was composed of Lebanese and Europeans and Americans, for instance, John Ferran, John Carswell, Arthur Frick and Roger van Gindertael. However, since the ninth Salon, the jury members have been mainly Lebanese nationals. Sometimes, the composition and preferences of the Jury were subject to heated debates. Particularly, the tension between abstract and figurative art was commonplace, reflecting some of the larger discussions concerning art in the region on a more general level.

The Salon d’Automne was open to all Lebanese artists regardless of their place of residence as well as to foreign artists living in Lebanon. Participating in the exhibition was considered to be prestigious as all the artists were required to go through a selection process. Some of the participating artists include Shafic Abboud, Aref El Rayess, Saloua Raouda Choucair, Paul Guiragossian and Nadia Saikali. Despite the prestige, throughout history, there have also been several artists, who occasionally boycotted the Salon for different reasons, including the preference of ‘Western’ (abstract) art at the expense of figuration, for instance, Rafiq Sharaf, Michel Basbus and Nicolas Nammar.

The Salon presents one of museums’ most important functions – exhibiting art and artefacts – and exemplifies how exhibitions can become important vehicles through which to form and influence public taste. Furthermore, as the Sursock Museum came to acquire art through the Salon d’Automne, we can also read a canon of Lebanese modern art through the exhibitions. This is particularly significant considering the aforementioned lack of a public modern and contemporary art museum in Lebanon, and that most of the art galleries that were active in Beirut during the 1960s and 1970s are long gone. The historical power of the Salon lies in its ability to present us a documentation of the development of Lebanese art history, and up until the tragic August explosion in Beirut, the power of the Sursock Museum had been to present that documentation in its permanent exhibition.

Images: Courtesy of the Sursock Museum.

Read more:

von Maltzahn, N. (2019). The museum as an egalitarian space? Women artists in Beirut’s Sursock Museum in the 1960s and 1970s. Manazir Journal, 1, 70-81.

The Salon d’Automne and Sursock Museum

The Salon d’Automne and Sursock Museum