Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World

Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World

In 1989, the National Museum of Women in the Arts reached out to Salwa Mikdadi, a curator and an art historian at the time, to update their files on Arab women artists. This encounter gave the initial spark of the exhibition Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World, which was developed further to take place at the museum. In 1993, the exhibition opened at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, co-organised with the International Council for Women in the Arts, which had been founded in 1990 by Salwa Mikdadi, with Etel Adnan, Laura Nader, and Lila Grace, and the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, established in 1980. The exhibition also toured in America, in states such as Georgia, Florida, and Massachusetts. Importantly, the exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue containing essays by authors such as Etel Adnan and Laura Nader, Shehira Doss Davezac, Todd B. Portefield, and Wijdan Ali.

The Exhibition Ethos: Approach and Artists

The exhibition Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World grouped together 70 artists from 15 countries, including Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Sudan, Tunisia, and the United Arab Emirates. The title of the exhibition was derived from women’s growing sense of power, a force to be reckoned with. The concept was divided into four curatorial streams: eponymous Forces of Change, Present Reflections, Rhythms of the Past, and Image and the Word. Through a wide range of themes tackling problems of daily life, civil war, armed conflict, human rights, occupation, and the environment, the influence of art movements, exploration of earlier artistic expressions, interpretations of Arabic calligraphy and the use of the written words as a mode of visual expression, the works were grouped together “to elicit admiration, outrage and amusement”. Furthermore, the works in the exhibition articulate resistance and the emergence of a new culture, that sometimes reintegrate layers of history and traditions. For instance, folkloric designs appear in the work of many artists who employ patterns and symbols to celebrate their culture, but also to give birth to original and unique visual expressions. The exhibition comprised works that date from 1947 to 1993, with pioneering artists such as Saloua Raouda Choucair and Inji Efflatoun, to contemporary artists such as Laila Shawa and Mona Hatoum. To illustrate the width of artists included in the exhibition, it is worth noting the following examples:

Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916-2017) was a Lebanese painter and sculptor, as well as one of the earliest abstractionists in the Arab region. After attending the American Junior College for Women (now the Lebanese American University), she studied natural sciences. Choucair was deeply fascinated by Islamic art and architecture, and pursued her research in that field through which she developed her abstract forms. She described her art as “a form embracing the spirit of Arabesque designs, with their mathematically calculated patterns.” Choucair’s Two = One (1947) is one of the featured works in the exhibition, presenting geometric abstract forms that are tangled to each other, creating a harmonious visual expression. Today, the work Two = One is part of Sursock Museum’s collection, damaged by a bomb during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), and again in Beirut’s recent explosion of August 2020.

Inji Efflatoun (1924-1989) was an artist, activist, and a prominent figure of her generation who advocated for political and social change in the 1950’s. Born into an upper-class family, Efflatoun had the privilege to pursue her art training with leading painter and filmmaker Kamâl al-Tilissâni, and quickly rebelled against social injustice and joined activist groups. Discussions apropos ideologies and class struggle led to her radicalisation and rupture from her upper-class milieu to advance on political and social concerns expressed through manifestations, publications, and paintings. In 1959, Efflatoun was arrested due to her political activities. During her four years of imprisonment, Efflatoun painted major works of women in prison. Her painting Prison 126 (1960) depicts a number of women sitting on the floor behind bars. Although the painting is banal, it depicts the daily struggle of Egyptian women in prison. After her release in 1963, she turned her focus to expressing the Egyptian character through the depictions of felahinsi (Egyptian peasants), workers, and other figures of resistance in the Arab region.

The Gaza-born artist Laila Shawa (b. 1940) is known for her political take on structural violence, turmoil, and resistance. In her practice, she tackles and portrays the harsh realities of the Israeli occupation. In Wall of Gaza (1992), the artist photographed the graffiti on the walls of Gaza as it appeared before it was obscured by the paint brushes wielded by Israel’s occupation army, and the large dollar signs which they used to cover such public expressions. Once the photographs were silkscreened onto canvas, she then superimposed geometric designs on them, trying to evoke a sense of order and accentuate the messages.

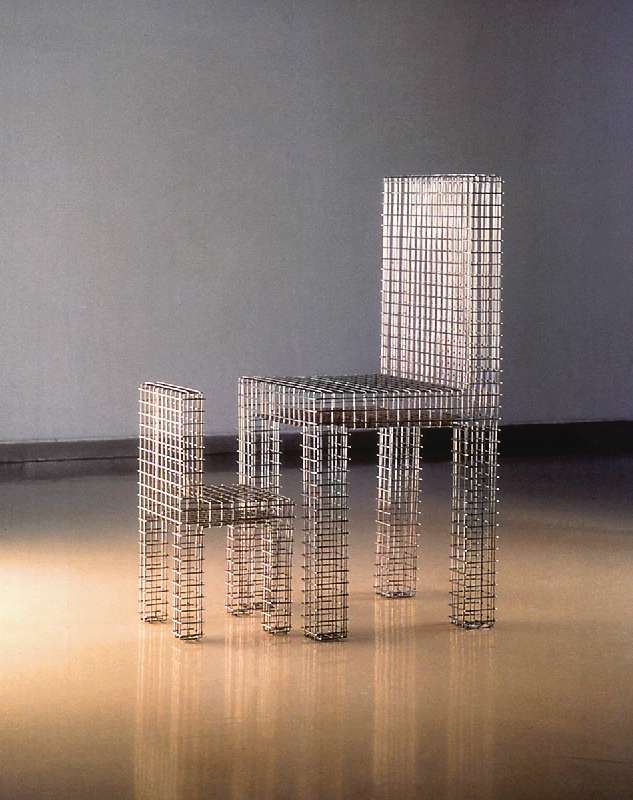

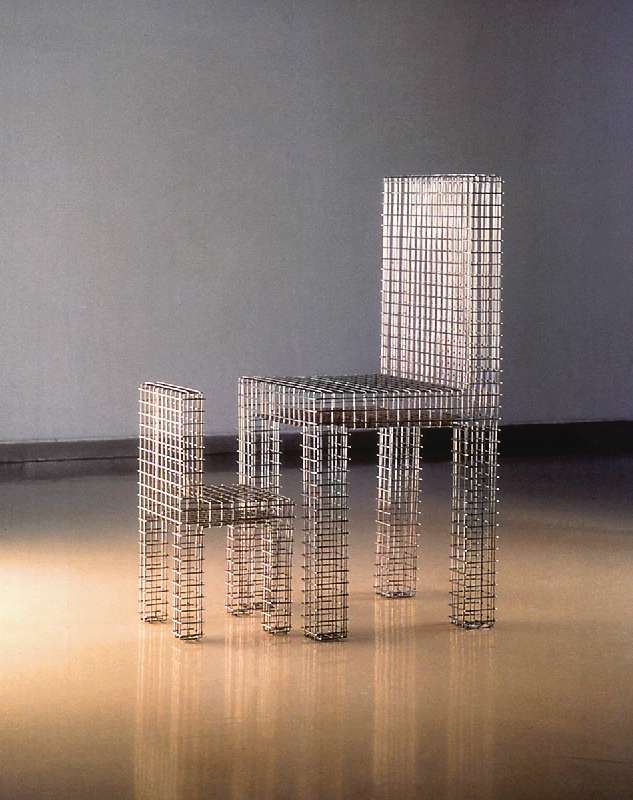

Mona Hatoum (b. 1952) is a Palestinian contemporary artist, born in Beirut. She moved to London in 1975 where she studied, worked, and lived for the last four decades. In her early career, Hatoum worked primarily with performance art which gained her international recognition. In the 1990’s, she moved away from this ephemeral medium to focus on sculpture, installation, furniture, and familiar objects with a minimal aesthetic. Untitled (1992) is an installation of two wire mesh chairs confronting each other, one is smaller than the other one. Hatoum introduced objects of the everyday, such as furniture, into her body of work on the basis of our relationship to these objects. As such, these two chairs refer to our bodies when they are absent. Thereby, the chairs are transformed into objects that are strange, threatening, and dangerous revealing uncertainty.

Historical Significance in the Canon of Art

The Forces of Change exhibition is particularly significant for three main reasons. First, it opened in 1994, only five years after the famous Magiciens de la terre exhibition organised by the Pompidou – the show that is considered to open a new era of globalisation in the art world as the show presented, for the first time, “non-Western” artists and celebrated their work, meaning displaying them as artists and not as craftsmen or exhibited their work in an ethnographic sense. At the same time, exhibiting modern art from “non-Western” countries was almost a non-existent practice: the very few examples include the London-based 200 Years of Lebanese Art show and the 20 ans, 20 artistes show at the Institut du monde arabe in Paris and Rabat. In this context, where contemporary art from “non-Western” countries was only beginning to appear at prestigious museums and modern art was almost entirely absent – bear in mind, in the 1990s the discourse on modernity was extremely focused on the West: non-western modernities were, at their best, seen as pale imitations of the “real thing”.

Second, the exhibition’s position, celebrating women as creators and contributors of the arts, thereby bringing them recognition and rewards from their respective countries and abroad, is historically unique: to our knowledge, there had only been one exhibition, Egyptian Women Painters Over Half a Century, organised by Inji Efflatoun in 1975, that hold a similar curatorial ethos. It is crucial to remember that although exhibitions had not explicitly discussed the role of women in the arts, throughout centuries, women have played significant roles in supporting the arts in the region. Some of the more recent examples include Helen Khal, who co-founded Beirut’s first commercial art gallery, aptly titled Gallery One, in 1963, Sheikha Hussa al-Salem al-Sabah and the Dar-al-Athar al-Islamiyyah in Kuwait and Wijdan Ali and her instrumental role in the creation of the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts in the 1970s and 1980s.

Third, the exhibition’s location in the United States is also important and ground-breaking. Although Arab art had been exhibited in the West already in the 1950s, regional cultural diplomacy was not as popular as it is nowadays with several mega-museums and other cultural projects being established in the Gulf and the Barjeel touring the United States. Considering this, organising an exhibition such as Forces of Change, was a remarkable, novel action. And, noting some of the recent shows with their inherently Western gaze, built on Imperialist and colonial assumptions, it still feels like a breath of fresh air, despite being almost thirty years old.

Featured image: Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World Exhibition Catalogue’s cover.

Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World

Forces of Change: Artists of the Arab World