In Conversation with Shireen Atassi

In Conversation with Shireen Atassi

Throughout the region private individuals and their ventures have shaped the art scene and cultural ecosystem. To examine these practices further, Mathqaf sat down with Shireen Atassi from the Atassi Foundation to talk about her family’s long-term support for Syrian arts and the work of their foundation.

Mathqaf: Could you tell us about the beginning of your story?

Shireen Atassi: My family comes from Homs, a small city in the middle of Syria. My mother, Mouna, and her sister, Mayla, wanted to start something together. In the 1980s they opened a book shop and in the attic, they showed a few works. A year or two later, they set up an art gallery in the same building. At the time, art was not really a thing in our family. My grandparents were landowners and they might have collected carpets and so forth, but definitely not art. This transition from a book shop to an art gallery and a meeting point for the intellectuals in Homs was very organic. In 1993, Mayla moved to Dubai and opened the Green Art Gallery there, whereas my mother opened the Atassi Gallery in Damascus. Between 1993 and 2010, the gallery in Damascus was very active: it didn’t only exhibit and organise symposiums and published books, but it was also a nexus or a meeting point for the Damascene intelligentsia, gathering poets, artists, filmmakers and architects. In 2012, my parents left Damascus and moved to Dubai, and in 2015 we started an art foundation. At the time, I was in a completely different line of business, working in a corporate environment. I quit my corporate job and we set up a foundation. My parents had collected art over the years since the 1980s, and their collection had moved to Dubai. During this time, at the height of the war in Syria, we thought it was important to show a different side of Syria in order to fight against the stereotypical view of war and killing, which is not representative of us as a society. We realised we wanted to and also needed to give back to the arts and culture community, so we registered as an art foundation and launched at Art Dubai in March 2016.

Mathqaf: We have gathered that the renowned Syrian artist Fateh Moudarres had a very important role for the Atassi Gallery.

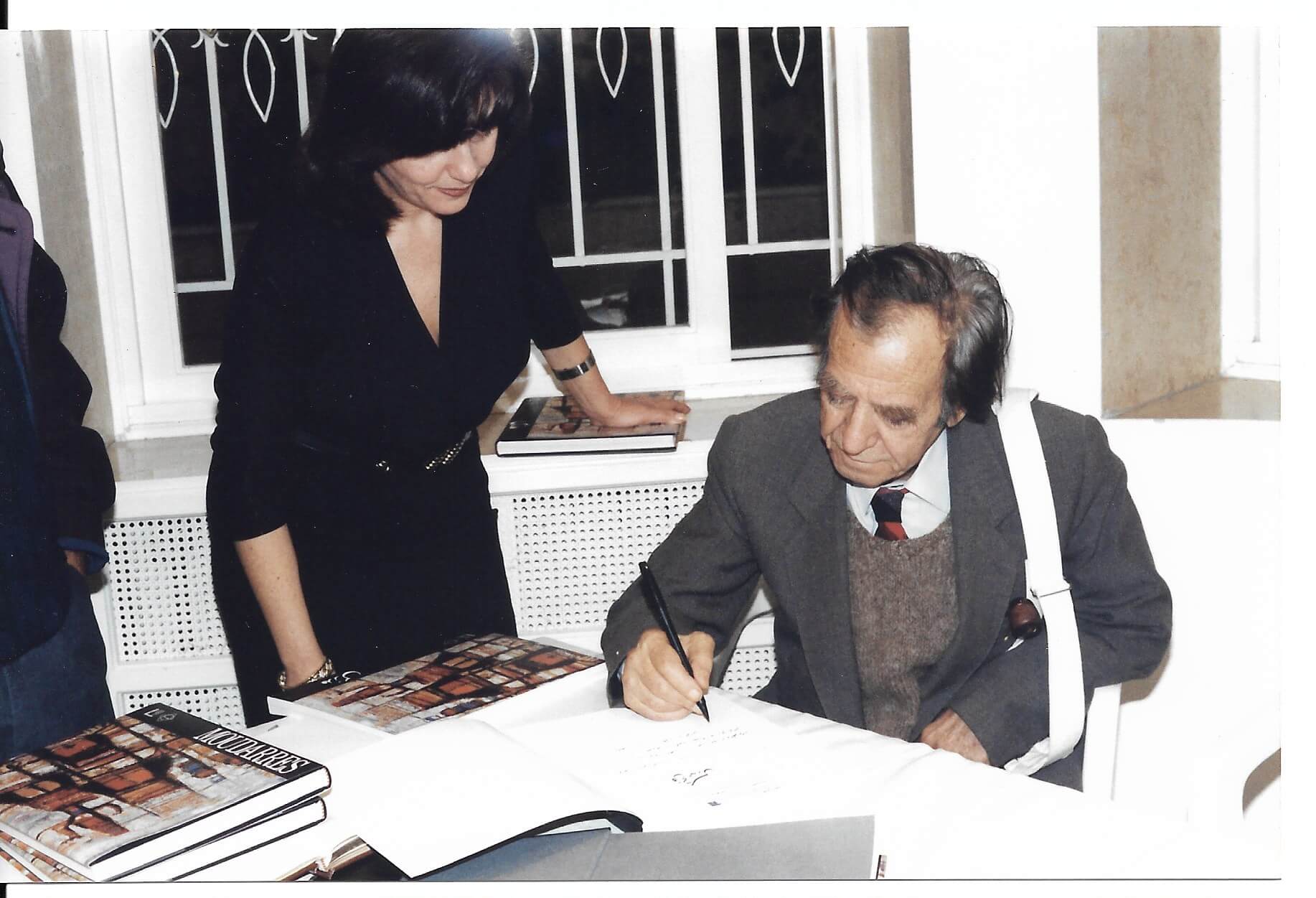

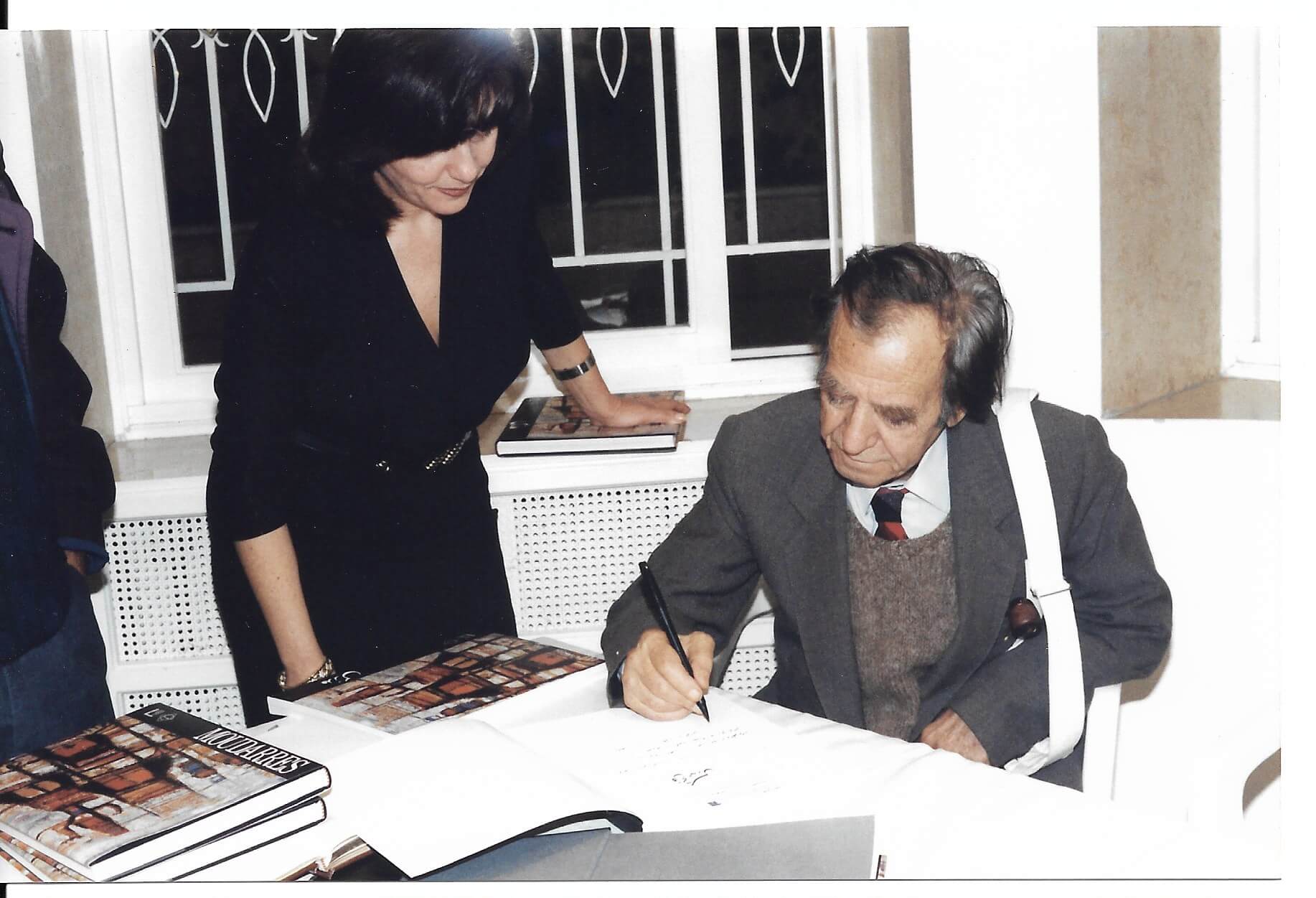

SA: Fateh indeed had a special relationship with the gallery and was a friend of my parents’. My mother published one of the very first monographs on him in 1996. In 1998, there was a symposium in the gallery between Fateh and Adonis, dealing with the relationship between painting and poetry: word and colour as the raw materials, the basics of poetry and art. The symposium was so interesting that the conversation had to continue, so my mother hosted both Fateh and Adonis at our house for three evenings, whereby Adonis interviewed Fateh on all sorts of things: art, life, motherhood, home, religion, politics. The idea was to publish their conversation in a book, but then Fateh died the following year in 1999 before the book materialised. Ten years later, however, my mother managed to publish this conversation to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Fateh’s passing in an Arabic book accompanied by images of his works on paper. Now, we are working on publishing it in English, because it is such a fantastic read and offers an in depth view into Fateh’s world.

Mathqaf: What does the Atassi Foundation do?

SA: The mission of the Foundation has matured over the years. In the beginning we wanted to promote and preserve Syrian art, but now we talk more about knowledge creation, advancement of knowledge and capacity building for artists.

Mathqaf: It sounds like there is an interesting parallel between the activities in the 80s and 90s and nowadays, especially when you use terms like ‘knowledge production’ and ‘advancing the art scene’. It also makes us think of the lack of modern art institutions in Syria: no national museum of modern art, just that department at the National Museum in Damascus. Right now, the art scene must not really be a priority of the regime either, which means that there is definitely space and need for private initiatives. At the same time, the tasks at hand are quite great: archiving, writing art history, presenting Syrian artists.

SA: Absolutely. The task at hand is indeed too large for one organisation to take on. As you said, there’s the department at the National Museum, and they have a big collection, but no one knows what happened to it. The government is certainly not active in the same way as private initiatives, who have been the more effective agents in supporting the Syrian creative community both in Syria and beyond. Sadly, there aren’t many such initiatives but to mention one, there is Ettijahat – an organisation that was set up in 2011 to support arts and culture from Syria. There is plenty of room for more players because I personally believe the sector requires far more than can be offered by a couple of organisations.

When we think about our role as a small, private, family-run initiative, we always ask, how far can we go? We are not supposed to single handedly preserve or document the art history of Syria – that should be a collective effort. The Atassi Foundation has a small publication, the Journal, that aims to fill the gap concerning art historical writing on Syria, with contributions from a variety of writers and researchers. It’s a small step, but nonetheless a step. Archives, on the other hand, are an important part of not only the collective memory but of knowledge creation, as archives are the basis of exhibitions, research, writing and curation. We are currently building the Atassi Gallery Archive, spanning from 1993 until 2010. We have more than 100 exhibitions and lots of different material on them: pricing lists, catalogues, pictures of openings and so on. In total, we have more than 3000 individual records. Everything has been now digitised and we are currently in the process of assessing publishing options and building captions.

Mathqaf: Would you say the foundation has shifted from exhibiting Syrian art to research-based activities?

SA: I don’t think the two are mutually exclusive, but rather complement each other. Exhibiting is really important because you are able to reach audiences. We have organised a few exhibitions in Dubai and all of them were very successful and representative of the Syrian art scene, either historically or contemporarily. Importantly, all our exhibitions were meant as a form of inquiry.

Mathqaf: What are your plans for the future? Are you, for instance, planning on acquiring a physical space for the foundation?

SA: No, we do not want a physical space, and this is for two reasons: the moment you have a physical presence, you become an event-driven or exhibition-driven venture. I think our role is so much more than that. Second, we have humble resources, and I think we use them more effectively without having a physical space. Permanent space in Syria, however, would be amazing, but it is not on the horizon for the time being. For our activities, I wish them to become more frequent. I also hope to move forward to the second stage of our archival project, when we move to publishing other archive collections related to Syria. This is obviously a major project, but fundamentally important for the foundation and for the Syrian art scene.

Check out the Foundation’s website here and follow them on Instagram here.

In Conversation with Shireen Atassi

In Conversation with Shireen Atassi