The Contested Modernity of Contemporary Islamic Architecture: A Case Study on The Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar

The Contested Modernity of Contemporary Islamic Architecture: A Case Study on The Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar

In the wake of the transition to modernity, postmodernity and the increasingly secular movement towards globalization, little has been done in developing contemporary Islamic architecture outside the parameters of religious mosques or shrines. The main cause for the lack of innovation is the adoption of western standards of architecture as a universal future urban infrastructure. This is the primary reason why cities like Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Doha carry a lot of similar characteristics to city landscapes of New York, London and Las Vegas. Such similarities in early modern architecture are even apparent in the holiest city to the Muslim community. As argued by Dr. Ali Abdul Raouf in his book titled: From Makkah to Las Vegas, buildings that now surround the Haram which include shopping malls, hotels, Abraj Al-Bait Tower and the Makkah Royal Hotel Clock Tower, all overshadow the Kaaba and carry no architectural link to Islamic tradition. What was even more of a shock to Dr. Abdul Raouf was that he found architectural similarities between the buildings surrounding the Haram in Mecca, and the buildings of Las Vegas casinos. In the context of different Gulf cities, one can argue that the product of western modernity is big extravagant monuments disconnected from their original context and forced upon the local communities. The question here becomes, what form can contemporary Islamic architecture take when it is faced with two extremes of western modernity on one hand and Islamic tradition on the other? Looking at the architecture of the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA) in Qatar, this research paper will argue that the future of contemporary Islamic architecture is one where modernity is contested to not only illustrate symbolic visual aspects of Islamic influence, but also practice values of urban development within a Middle Eastern context. To explore this topic, the following sections will highlight three important elements of MIA’s architecture: The already existing setting of the architecture (The Theater), The design of the building (The Performance) and finally the relationship between the architecture and the local community (The Scenes).

The Theater: The Movement from Function to Symbolism

Qatar is a country that has gone through a rapid period of modernization, a process that transformed the city’s landscape in a matter of years. According to Dr. Abdul Raouf, “In the late eighties and early nineties, a considerable number of Middle Eastern cities including Gulf cities moved swiftly into a more westernized architecture to declare its thrive towards gaining international identity” (Abdul Raouf 2010:62). However, such thrive has often been attached to a growing concern for the future of Qatari culture as well as the local community. As Dr. Nasser Rabbat states:

The new wealth of the gulf patrons, their deeply religious and conservative outlook, and their fervent quest for a distinct political and cultural identity in the sea of competing ideologies around them combined to create a demand for a contemporary yet visually recognizable Islamic architecture (Rabbat 2012:10).

This demand for contemporary Islamic architecture, along with “The unique cultural and geopolitical position of Qatar, … created a rich soil for architectural experimentation where a considerable number of physical interventions have emerged toward originating identity and in search for meaning” (Salama 2012: 95). What resulted from such experimentation is a clash of modernity; a form of modernity that pushed architects to incorporate “various historical elements dubbed ‘traditional’, ‘Arabic’ or ‘Islamic” (Rabbat 2012:10), in order to merge the contemporary modern with the traditional ancient, the old with the new, the Western with the Eastern. The first of such attempts in Doha, is the Supreme Education Council built in 2002 (see figure 1), where a mosque structure is embedded into the early modern architecture of the building.

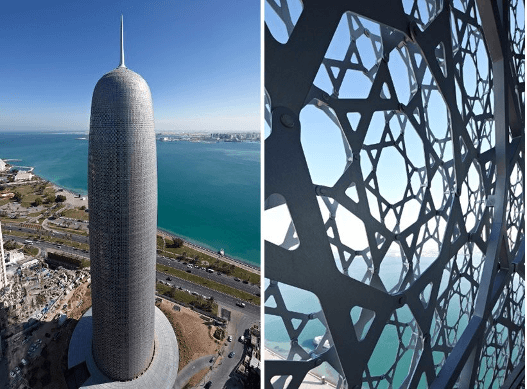

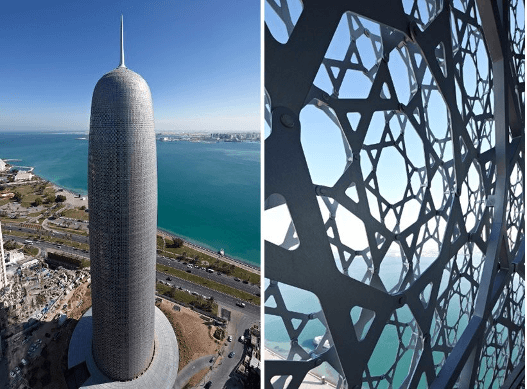

The example above illustrates how architectural experimentation aimed at integrating modern and Islamic elements within the design however, the two elements were separated in the sense that one design was incorporated into the other. The second experimentation in Doha was by the renounced French architect Jean Nouvel when he created the Doha Tower (see Figure 2).

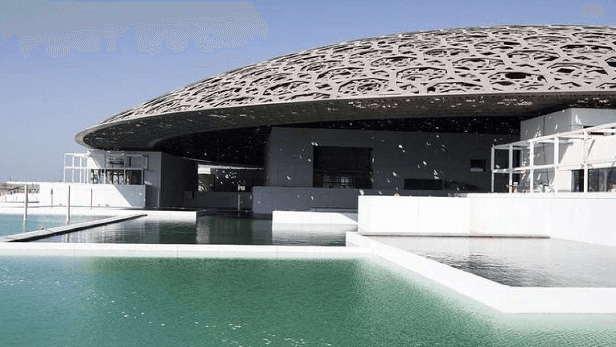

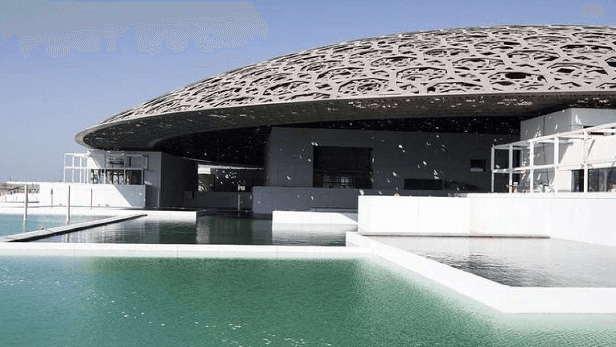

Nouvel’s design of Doha Tower is claimed to use Islamic geometric patterns in illuminating the interior of the building with natural light. Nouvel’s experiment with Doha Tower eventually lead him to design the Louvre Museum in Abu Dhabi (see figure 3).

What the previous examples illustrate is how architectural experimentation in Qatar has moved into attempts of integrating elements dubbed as ‘Islamic” into the substance of contemporary architecture. Dr Karen Exell, Senior Museum development specialist at Qatar Museums states, “The rhetoric of fusing the traditional and the modern represents the region’s approach to modernity, an agenda of retaining cultural identity in balance with aspects of a more secular modernity” (Exell 2016b: 2). In other words, the narrative served by early modern architecture in the gulf is the agenda of creating a modern secular state capable of incorporating Western practices of architectural progression towards modernism. Educational and cultural institutions can then be seen as tools that facilitate a regionally competitive race to modernity and global recognition (Rizvi 2015: 155). Thus, contemporary architecture found itself in a position where it had to serve the purpose of creating a balance between western influence and a distinct or regionally familiar architectural identity. In that sense, architecture became a tool of visually representing a selected Qatari identity that in the case of the Museum of Islamic Art, is claimed to be rooted in Islamic heritage. Dr. Mariam Ibrahim AI-Mulla comments on Qatar’s current architectural development by stating, “Architecture in Qatar is witnessing the movement from a reflection of a simple life to more complex themes, as life there is experiencing increasing change … Thus, architecture in Qatar is moving from the merely functional to the symbolic” (AI-Mulla 2013: 217). This is exemplified in contemporary buildings such as the Qatar National Museum designed by Jean Nouvel as the structure is symbolically designed after a desert rose connected to the archeological site of the previous royal palace (Shown in figure 5).

Not to forget the symbolic restoration and modernization of Souq Waqif, a historic Qatari marketplace now functioning as a recreational and shopping destination (shown in figure 4). Ultimately, the most prominent architectural statement embodied within such contemporary buildings is that of the Islamic Art Museum, designed by Pritzker Prize-winning Chinese American architect I.M. Pei. Commenting on the architecture of the Museum of Islamic Art, Dr. Karen Exell states, “This was a master stroke of cultural diplomacy, and an example of regional agency in a globalized world [by] utilizing an existing medium of Western communication – the museum – to attempt to change the discourse from within” (Exell 2016B: 5). In other words, the museum attempts to bridge the gap between western disciplines of Islamic art history and regional practices of religious and political identity formation. What resulted from this attempt is a moment of transition in architectural development in Qatar where buildings became a symbolic gesture that attempts to reflect a selected identity of the local community alongside advancing the narrative of such identities to global audiences. The next section will highlight I.M. Pei’s attempt of incorporating Islamic architectural elements within the design of the Museum of Islamic Art.

The Performance: Contemporary Islamic design and the Museum of Islamic Art

Before Pei started working on designing the project, he embarked on “visits to the Grand Mosque in Córdoba, Spain; Fatehpur Sikri, a Mughal capital in India; the Umayyad Great Mosque in Damascus, Syria; and the ribat fortresses at Monastir and Sousse in Tunisia, [where] he found that influences of climate and culture led to many interpretations of Islamic architecture” (DesMena 2010). However, he drew most of his architectural inspiration from the Sabil of the Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun in Cairo. According to I.M. Pei:

I believe I found what I was looking for in the Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun in Cairo (876-879). The small ablutions fountain surrounded by double arcades on three sides, a slightly later addition to the architecture, is an almost Cubist expression of geometric progression from the octagon to the square and the square to the circle. This severe architecture comes to life in the sun, with its shadows and shades of color (Abdul Raouf 2010:64).

In other words, the main focus of Pei’s inspiration was on working with natural light to stress the geometry of the building. As claimed by Pei, this inspiration came from the Ahmad ibn Tulun Sabil (fountain) placed in the central courtyard of the Mosque (see figure 6).

This use of shade and light as depicted in figure 6 and figure 7 of the Sabil and MIA, claims to facilitate “a dynamic quality and extend the designs and patterns, creating strong contrasts of planes and [gives] texture to sculpted stone, as well as stocked or brick surfaces” (AI-Mulla 2013: 202). In other words, the shadows and light mixed with the geometry of the building creates an illusion of differing shades of color and depth. This use of natural light extends to aspects of the internal design, as Pei claims to have borrowed techniques apparent in the interior domes of both the Sabil and the Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun (shown in figure 8 & 9).

What Pei noticed from the dome, is that natural light was used as an element to highlight both the interior as well as the exterior geometry of the building and its architecture. This technique enabled the building to be seen in different light during different timings of the day, as indicated by the contrast between figure 9 and figure 10.

What resulted from such influence, is Pie’s own take on interior illumination in the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar, as shown in the following figure 11 and figure 12.

As shown in the figures 11 and 12 above, Pei’s design is constructed to facilitate natural illumination in highlighting the geometric patterns inside the stainless-steel dome of the museum. Another point of influence is the geometric pattern on the ground of the main atrium in the museum as it resembles the same pattern used for in the mosaics of Alhambra palace in Spain (see figure 13 and 14).

The resemblance continues in major and minor details of Pei’s design as a reminder to the visitor that the building is ‘Islamic’ yet fundamentally modern. Therefore, the fundamental element of Pei’s design is that it incorporates stylistic features from different Islamic monuments into a modern design.

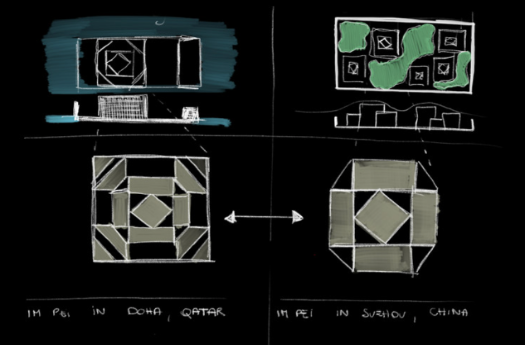

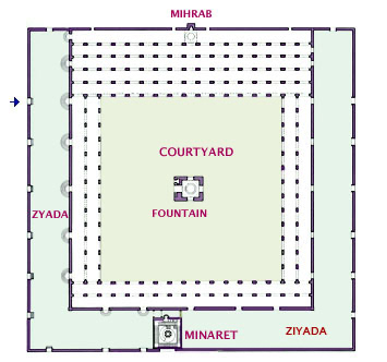

As shown in the previous passage, Pei’s design is not a replica of the palaces or mosques, nor is it a dramatic redesign of their features, Instead the design is contemporary in nature, placing the building in between influences derived from earlier monuments and Pei’s own style. The question here becomes, is the Islamic elements of MIA incorporated into a modernist design or is the modernist elements incorporated into an Islamic design? According to Dr. Mariam Ibrahim AI-Mulla, “the architect hoped to give the illusion that he was creating an Islamic building by drawing on many influential themes. Thus, Pei was diligent in moving between sources of inspiration and allotting them places in his design” (AI-Mulla 2013: 206). In other words, Dr. Al-Mulla, argues that Pei’s design struggles to uphold its claim as a monument that represents contemporary Islamic architecture mainly because it borrows more from modernism than it does from ‘Islamic’ practices. To answer the question in regard to Pei’s design, we have to look exclusively at what inspired his modernist side of MIA’s architecture. The first point of comparison is that of the Suzhou Museum, a museum of ancient Chinese art designed by I. M. Pei in 2006 (two years before MIA, shown in figure 15).

The resemblance between Pei’s design of MIA and the Suzhou Museum suggest that Pei’s previous project influenced his depiction of a contemporary ‘Islamic’ architecture. According to Wahyu Pratomo & Kris Provoost in their article about Pei’s Suzhou Museum:

The design clearly played a significant role in the later work he did on the Museum of Islamic Art. While the latter is larger in scale, we notice a comparable language of orthogonal and diagonal lines. The floor plans of both buildings have strong similarities. (Pratomo 2017).

In other words, there are elements of influence from Pei’s previous designs within the Islamic Art Museum, elements that critics did not overlook when discussing the building’s attempt of distinguishing a hybrid architectural identity. What this suggests is that elements of Islamic style and modernism are contested within a single architectural design as a distinction can be drawn between Pei’s design and his influence from Islamic styles.

The concern here is that Pei’s own style can overshadow the styles incorporated as ‘Islamic.’ Dr. Al-Mulla argues that, “Abstraction in the MIA’s architecture is not a reflection or a mirror of any one particular building; the abstraction in the building is a generation of a model without a real origin” (AI-Mulla 2013: 212). However, one can argue that this ‘abstraction’ is a characteristic feature in the history of Islamic architecture where regional styles emerged to build on the classical style of the first Mosque. Such alternations enabled the creation of new styles and the continuity of regional styles, all within the transregional category of Islamic architecture. Addressing the Islamic styles in India Dr. Finbarr Flood states:

the appropriations and improvisations intrinsic to bricolage and its ability to generate new meanings from pre-existing materials (and indeed vocabularies) exemplify the unstable and fluid nature of any sign, undermining the notion of a transcendental signified that is intrinsic to mimetic or reproductive modes of translation (Flood 2009: 183).

In other words, the appropriation of different sighs in Islamic architecture has led to the creation of styles independent from the original appropriated monument. If we apply the same principle in Pei’s design, we can argue that the adoption of Pei’s modernist style created an entirely new style independent from the monuments it is influenced by. Therefore, the Islamic element in Pei’s design is that It facilitates modernity to illustrate symbolic visual aspects of Islamic influence that resulted in the creation of a new style independent from Pei’s style and ancient Islamic styles.

The Scenes: Where are the minarets?

When first entering the Museum of Islamic Art, the Saudi private art collector, Abdullmohsen AI-Mahmoud expressed his disappointment by stating:

When I entered the museum, I felt as if I was entering a ministry of defense with all the iron interior in evidence. I cannot feel the presence of the Islamic spirit in this architecture. This building does not provide any picture of Islam. Where are the minarets? … The designer had in this square building four directions. He could have filled each direction with a picture of Islam from various former Islamic areas, Islam in Europe, Islam in the Far East and Islam in the Middle East for example (AI-Mulla 2013: 215).

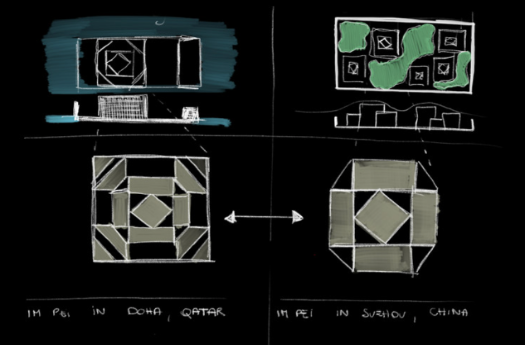

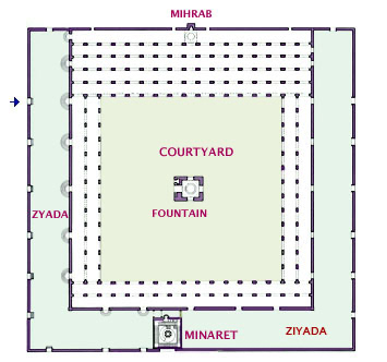

What the above quote illustrates is that minaret is an important element for visitors to associate the building with a mosque structure. However, as the structure is designed after the fountain of the Mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun, the minaret would have to be situated outside the fountain. If we look at the plan of the mosque of Ahmad Ibn Tulun (see figure 18), we can notice how the Sabil (fountain) is located in the center of the courtyard with the minaret in its background and the mihrab in its foreground.

If we draw a line between the mihrab, fountain and minaret, we can get a sense of orientation of the entire structure. Therefore, drawing a connection between a minaret and the Museum of Islamic Art, would give it a sense of orientation within the city of Doha. This section will thus attempt to explore the significance of MIA’s location and orientation in relation the city of Doha, its surrounding architecture and community.

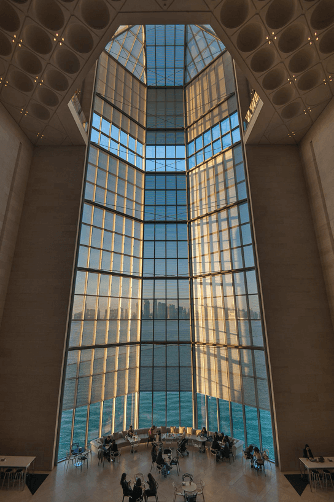

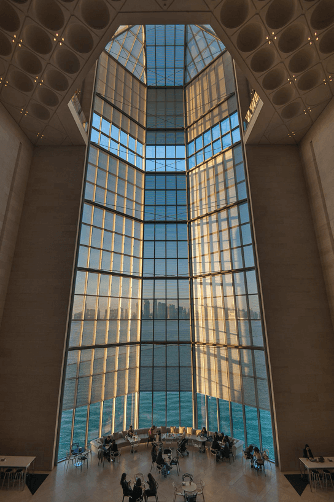

What is perhaps less noticed about the Museum of Islamic Art, is that the structure of the museum creates a window that points to two significant points in the city. The first and most apparent point is the skyscraper landscape of Doha’s West bay area (figure 19).

When entering the museum visitors are greeted by the view through a window that could be seen from all different floors of the museum. The second view, points towards Abdullah Bin Zaid Al Mahmoud’s Islamic Cultural Center and the area known as ‘old Doha,’ this is also where one can see the resemblance between the museum and the mosque of Ibn Tulun (shown in figure 20 and 21).

Contrary to the Museum of Islamic Art, the design of the Abdullah Bin Zaid Al Mahmoud’s Islamic Cultural Center is “inspired by the AI-Malwiya minaret of the great Mosque of Samara in Iraq” (AI-Mulla 2013: 58). However, this brings us to a discussion on the minaret of the Mosque of Ahmed ibn Tulun and its relationship to the Mosque of Samara in Iraq. According to Dr. Tarek Swelim in his article, titled, The Minaret of Ibn Tulun Reconsidered, “Al-Maqrizi, while quoting the historian Qudai (d. 454/ 1062), states that the mosque was built after the style of the great Mosque in Samarra, and likewise the minaret” (Swelim 2000: 79). Here I argue that regardless of whether Pei intended for his museum to be seen in the context of the Islamic Cultural Center or not, both monuments engage in an art historical commentary on the state of Islamic architecture. This commentary is shown in how the minaret of the great Mosque of Samara was appropriated into the minaret of the Mosque of Ibn Tulun and later both monuments were further appropriated into the Islamic Cultural Center and the Museum of Islamic Art. This appropriation creates a continuity in Islamic architecture, one that is not bounded to ancient historical narrative, but rather to contemporary challenges of defining what constitutes contemporary Islamic architecture. There is a symbolic resonance in those two building being in close proximity to one another as they resonate discussions on the role of Islamic influence and the distribution of architectural styles in the past, present and future.

One can see that the location of the museum was strategically chosen to be situated between two symbolic areas. The first area signifies the modern economic development of Qatar while the other area signifies the traditional side of Doha. According to the design magazine for Middle East and North Africa, “Declining to build the structure on any of the proposed sites along the Corniche, Mr. Pei suggested a stand-alone island [to] be created to ensure future buildings would never encroach on the Museum” (DesMena 2010). As Pei putts it himself, “I didn’t choose the location, I made it. I found it very tempting to do this!” (Abdul Raouf 2010: 65). Dr. Abdul Raouf explains the decision of creating the stand-alone Island for the museum as an attempt “to ensure that the museum should never be overwhelmed by the skyscrapers leaping up all over Doha” (Abdul Raouf 2010: 65). However, one can argue that Pei was attempting to create an architectural dialogue between his monument and the city it is placed in.

This division between the traditional and modern side of Doha provides a commentary on the state of urban development in the country and the communities effected by such development. The main group of people effected by the city’s transformation to modern architectural buildings are low-income working-class residents. According to Dr. Exell:

Sites of social integration are limited, with newly fabricated public leisure spaces such as shopping malls … allowing Qatari, Arab and Western residents to mix, but excluding South Asian construction workers and similar low status foreign males. Parts of Doha, such as the Msheireb area [located in old Doha], inhabited until recently by these latter groups, are being reclaimed for Qatari nationals (Exell 2016A: 262).

In other words, in order to build museums such as the Qatar National Museum in the traditional side of Doha, the social fabric of the city had to be altered to accommodate such change, pushing low income residents outside of the city and into the suburbs. This also created a lack of affordable public leisure spaces for these communities. Here I argue that the decision to build the museum on a reclaimed island served the purpose of paying respect to the remaining resident communities in old Doha. This is shown in Pei’s design of the artificial land surrounding the museum to be made into a public park that is larger than the museum space itself.

What the park illustrates, is an attempt to give public space back to the communities that were most effected by the country’s development towards modernity. According to Dr Abdulraouf:

Based on a series of interviews with visitors, MIA Park proved to be the primary destination for visitors. The compilation of MIA Park visitors interviewed draws attention to an interesting fact – most of the park’s visitors came to enjoy the open spaces, green areas, waterfront promenade and the city’s astonishing holistic views … It is clear that the purpose of museums for Qataris is not necessarily to merely view the collections but to experience the space and socialize near the monumental architecture (Abdul Raouf 2016: 86).

In other words, it is public value that ultimately determines the utility of the Museum of Islamic Art. Just as mosques served the purpose of spiritual fulfilment for the Muslim community, the Museum of Islamic Art attempts to offer an alternative public value. This is where one can argue that the future of contemporary Islamic architecture is one where modernity is contested to not only illustrate symbolic visual aspects of Islamic influence but also practice values of urban development within a Middle Eastern context.

Conclusion: Mosques, Museums and Public Value

In conclusion, this paper attempted to illustrate the values and practices associated with creating a standard for contemporary Islamic architecture. The first step towards contemporary architecture was initiated in Qatar by transitioning from functionalism to symbolism that attempts to reflect the identity of the local community while at the same time advancing the narrative of globalization. This symbolism has led to the Museum of Islamic Art’s design as a building that does not only illustrate symbolic visual aspects of Islamic influence but also practice values of urban development appropriate for its context. This has been done by creating architecture that is both culturally and socially aware of context of the city it is placed in. The experimentation here is one that attempts to fit contemporary architecture within the city as opposed to the city fitting contemporary architecture. Finally, the Museum’s park attempts to offer solutions to urban problems caused by the construction projects as reclaiming land for museums creates a paradox where these institutions alienate the communities, that claim it serves. The park then acts as an attempt to introduce spatial public value that serves a wider range of audiences, once that are not served by museums or galleries associated with the elites.

Work Cited

Abdul Raouf, Ali A. “One nation, one myth and two museums: heritage, architecture and culture as tools for assembling identity in Qatar.” Representing the Nation. Routledge, 2016. 95-110.

Abdul Raouf, Ali A. The role of museum’s architecture in Islamic community: museum of Islamic art, Doha. Journal of Islamic Architecture, 2010, pp. 60-69.

AI-Mulla, Mariam I. Museums in Qatar: creating narratives of history, economics and cultural co-operation PhD Thesis Submitted at the University of Leeds: School of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies, 2013, pp. 1-377, pdfs.semanticscholar.org/515d/7628ebdfad84e7cc7dc7a637ae6061c24d29.pdf.

DesMena. Museum of Islamic Art, Doha by I. M. Pei. 2010, desmena.com/2010/07/museum-of-islamic-art-doha-by-i-m-pei/.

Exell (A), Karen. “Desiring the past and reimagining the present: contemporary collecting in Qatar.” Museum & Society, Volume 14, 2016, pp. 259- 274.

Exell (B), Karen. Modernity and the Museum in the Arabian Peninsula. London, Routledge, 2016.

Flood, Finbarr Barry. Objects of translation: material culture and medieval “Hindu-Muslim” encounter. Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2009. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.31437.0001.001.

Pratomo, Wahyu, and Kris Provoost. Why IM Pei’s Museum of Islamic Art is the Perfect Building to Suit Doha’s Style, ArchDaily, 16 Mar. 2017, www.archdaily.com/867307/why-im-peis-museum-of-islamic-art-is-the-perfect-building-to-suit-dohas-style.

Rabbat, Nasser. “What is Islamic architecture anyway?” Treasures of the Aga Khan Museum: Architecture in Islamic Arts, edited by Margaret S. Graves and Benoît Junod, Journal of Art Historiography, issue 6, 2012, pp. 1- 15.

Rizvi, Kishwar. The Transnational Mosque: Architecture and Historical Memory in the Contemporary Middle East, University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Salama, Ashraf. “Narrating Doha’s contemporary architecture: the then, the now – the drama, the theater, and the performance.” Middle East: Landscape, City, Architecture, edited by Josep Luis Mateo, Krunoslav Ivanisin, DAP – Digital Architectural Papers, 2012, pp.94- 101.

Swelim, Tarek. “The Minaret of Ibn Tulun Reconsidered.” The Cairo Heritage, edited by Doris B. Abouseif, Cairo, The American University in Cairo Press, 2000, pp. 77-91.

The Contested Modernity of Contemporary Islamic Architecture: A Case Study on The Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar

The Contested Modernity of Contemporary Islamic Architecture: A Case Study on The Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar