The history of art institutions in West Asia and North Africa begins with…

Mawadah fel Zaman: Five Women of WANA Modern Art You Should Know About.

Mawadah fel Zaman: Five Women of WANA Modern Art You Should Know About.

More often than not, women are overshadowed in the art world. And while there have been strides for equality, I worry West Asian and North African (WANA) women are still being overshadowed. Discovering art by women in the region opened up a whole new world of expression and intersectionality for me, giving me the ability to grasp complex identities and see work about struggles parallel to mine. These artists have entranced me in their ways of capturing life poetically, and I think their work deserves to be honoured just as much as their male counterparts. Here are five of my favorite WANA women of modern and contemporary art.

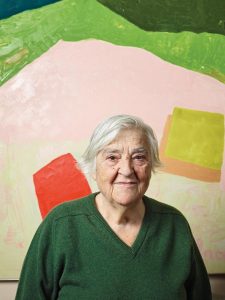

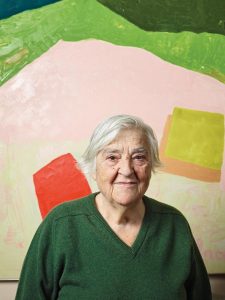

Etel Adnan (1925)

Etel Adnan is one of the most celebrated contemporary Arab-American authors, as well as a prominent figure in modern Arab art. Her paintings capture her relationship with space and its fluidity, having lived between Beirut, Paris, and California and watched these cities reshape and change over the past several decades. Adnan’s work is expressive despite its abstractness, usually depicting landscapes or what she describes as “not a particular landscape—it is maybe a memory of a particular landscape”. Mountains and suns painted in vibrant colors with the most hopeful undertones, canvases hosting intersections between cultures and a spiritual connection with environments.

“My painting is very much a reflection of my immense love for the world, the happiness to just be, for nature, and the forces that shape a landscape,” she says.

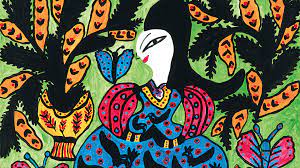

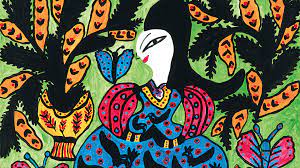

Baya Mahieddine (1931-1998)

Baya Mahiedienne, or simply just “Baya”, is one of my absolute favourite artists. I first learned about Baya in an article crediting her for being an inspiration to Picasso and Matisse (there’s a very apparent theme of artists from European countries being “inspired” by people who were being actively exploited by said European countries). Born in Algeria, Baya was orphaned at the age of 5 then adopted in her teens by Marguerite Camina Benhoura, a French woman that further facilitated her interest in art and led to spending parts of her adolescence in France, where her art caught the eyes of art dealers and surrealists. At the early age of 16, Baya’s artworks were shown at Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme in Paris. Baya’s paintings are dream-like; a world devoid of the male gaze. She painted women, nature, and animals in gouache, often using patterns and motifs that referenced her Algerian heritage. Her paintings illustrate harmony and joy, easily being described as a fairytale. Many of these fairytales were inspired by her childhood imagination, which I assume, could’ve acted as a refuge from her turbulent early years. She once said, “When I paint, I am happy and I am in another world.”.

Tahia Halim (1919-2003)

Tahia Halim was one of the pioneers of the Modern Expressive Movement in Egyptian Art in the 1960s. After the Suez Crisis of 1956, she abandoned stylistic teachings of the Western academy and created her own movement that valued expressionism, which used Coptic influences, and stayed true to its subjects. Her poetic and folklore-ish approach honors and expresses the characteristics of Egypt. In 1962, she joined a group of artists on a trip to Nubia, which became a turning point for her and her work. Halim became devoted to capturing life in Nubia, attempting to immortalize the rich culture of villages that would soon be drowned by Nasser Lake. Halim painted scenes so full of life and love, leaving viewers heartbroken knowing these Nubain communities have been displaced and much of their rich culture is now lost.

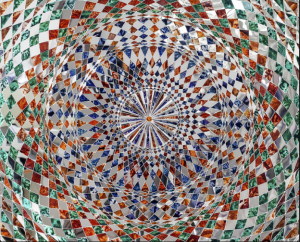

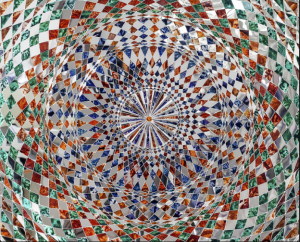

Monir Farmanfarmaian (1922-2019)

Farmanfarmaian is one of the most prominent Iranian contemporary artists. Although she did very well in the Western art world, even befriending familiar names such as Warhol and Koons, her work is characterised with Islamic and Iranian elements. In the 1970s, she visited the Shah Cheragh Mosque in Iran and was forever changed by the space. In her memoir, she described her visit saying: “The very space seemed on fire, the lamps blazing in hundreds of thousands of reflection (…) It was a universe unto itself, architecture transformed into performance, all movement and fluid light, all solids fractured and dissolved in brilliance in space, in prayer. I was overwhelmed.”. This transformative experience inspired her to look into the symbolism of shapes and Sufi cosmology, which eventually led her to develop a style that ties western abstraction by Islamic geometric symbolism resulting in stunning glass mosaics. Her arranged compositions of glass create a dance of light, reflection, and form. Farmanfarmaian is credited to be the first contemporary artist to reinvent Ayeneh Kari, a traditional Iranian craft of finely cutting glass and assembling them into complex shapes and intricate patterns.

Lalla Essaydi (1965)

Essayadi grew up between Morocco and Saudi Arabia, which inevitably led her to explore her experiences as a woman through the context of these cultures. Through her work, Essaydi revisits her Morrocan girlhood, reclaiming Orientalist imagery and using them to challenge viewers to resist the stereotypes and western narratives of the “orient”. Using photographs with Islamic calligraphy done in henna, Essaydi creates scenes that challenge notions of authority and cultivates a space for discussions surrounding gender, religion, diaspora, tradition, autonomy, and more.

I remember seeing her work for the first time, a painting of a girl probably not much older than I was, laying on her side and every inch of the view inscribed with henna calligraphy. The girl’s gaze struck me most. In orientalist paintings, women are merely subjects, stripped of their autonomy and their stories lost through the white man’s brushstrokes. This piece couldn’t be any less devoid of depth, I looked straight into the girl’s eyes and felt as if she were looking back into mine, almost acknowledging our shared struggles. North African/Muslim/Arab girlhood is a sea of complexity, and Essaydi’s art beautifully explores the swim through.