More often than not, women are overshadowed in the art world. And while…

Speak up for Arab Art

Speak up for Arab Art

Two decades ago my interest in modern Arab art was sparked at an unlikely venue. As my mother Nama bint Majid, my late father Saoud bin Khaled (1939-2005) and I were strolling alongside the northern bank of Dubai Creek, my eyes caught a sign that read “Art exhibition: Ismail Shammout and Tammam Al Akhal”. It was spring 2002. The venue was the conference hall of the Dubai Chamber of Commerce, a blue triangular glass building that was completed seven years earlier by Japanese architecture firm Nikken Sekkei. Upon entering, we encountered numerous large paintings by the artist couple. The figurative nature and historic content allowed for viewers who were not trained in art to recognise individuals, locales and events. I hadn’t realised what a treat that was until years later. During this period, there were scant exhibitions and resources for those interested in Arab art. Exceptions in the UAE included Green Art Gallery in Dubai (founded 1995), the Emirates Fine Art Society (founded 1980), the Sharjah Art Museum (founded 1997) and Abu Dhabi’s Cultural Foundation (founded 1981).

Today there are numerous books and catalogues on Arab art, there are internet resources and social media accounts, there are auctions and exhibitions, as well as collectors and scholars whom one can consult. And yet, Arab art remains largely within the margins of peripheral thinking, and has not been accepted widely yet. Young Arabs don’t recognise paintings by their modern masters as Westerners would recognise Starry Night for instance. In fact, there are Arabs who seem to equate knowledge of Western art with being “worldly”—much like speaking English is seen by some Arabs as being educated. This partly stems from decades if not centuries of a relentless Western barrage of cultural output, aided by colonial history, military force and the soft power of Hollywood film studios that has only intensified in recent years. For Arab art to escape the label of elitism, a major change is needed in the way it is perceived and consumed by the general public. Arab government efforts to support local art, however meagre, must be encouraged and reinforced by a change within all of us. And so to young Arabs who are willing to embrace the best of our culture, I would say this: take pride in Arab art. Do not succumb to the defeatism of others. Do not be discouraged by those who do not know your culture or do not appreciate its beauty.

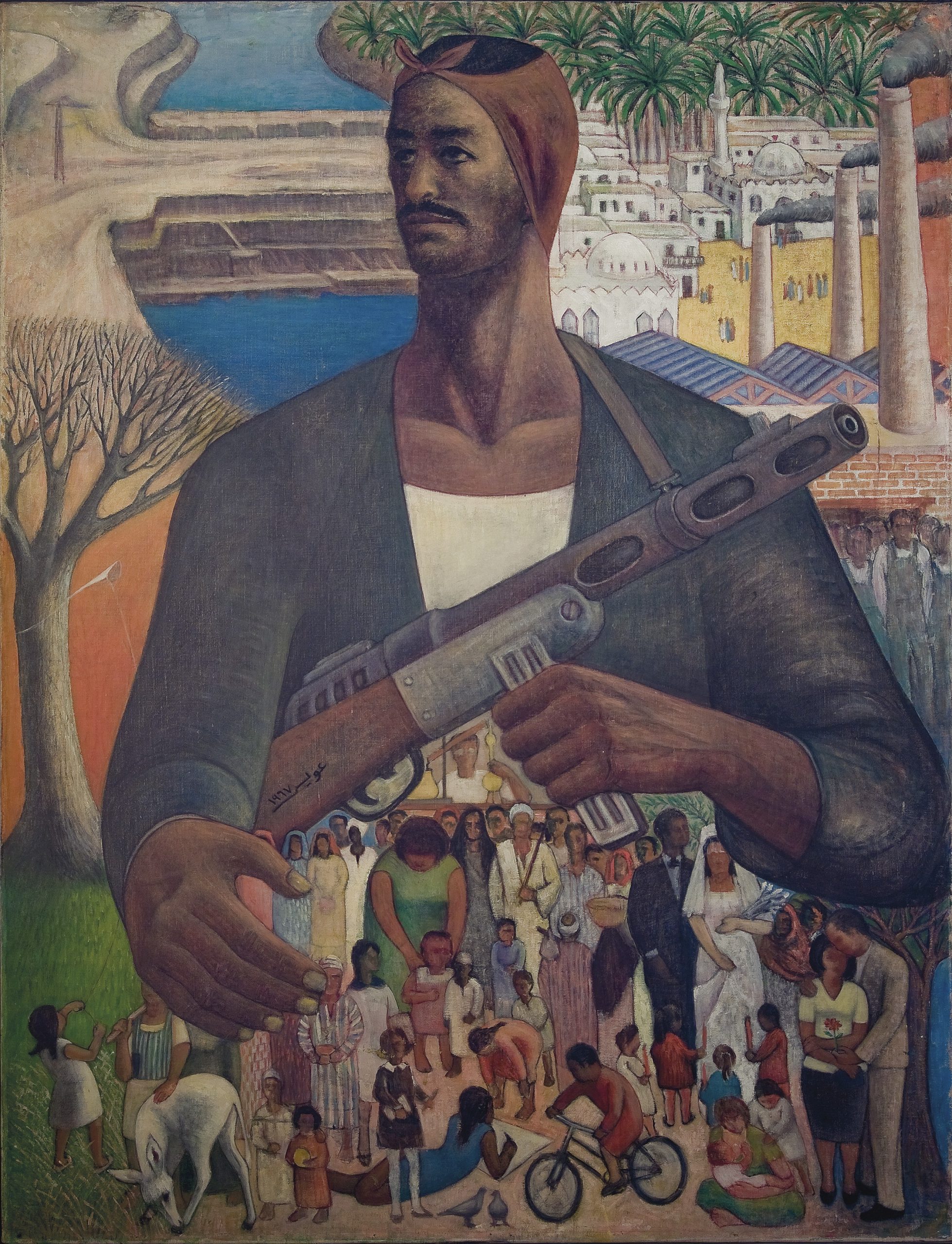

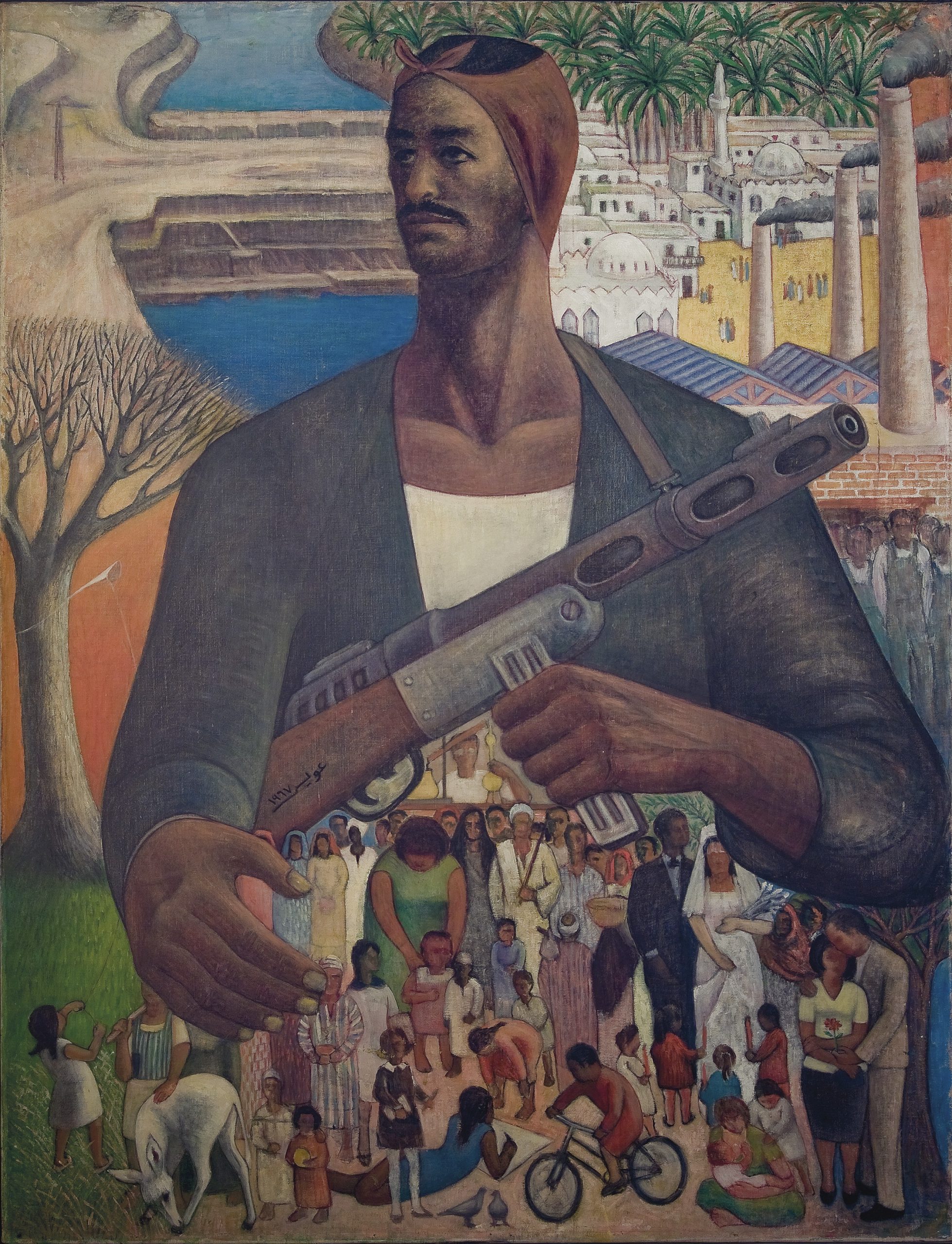

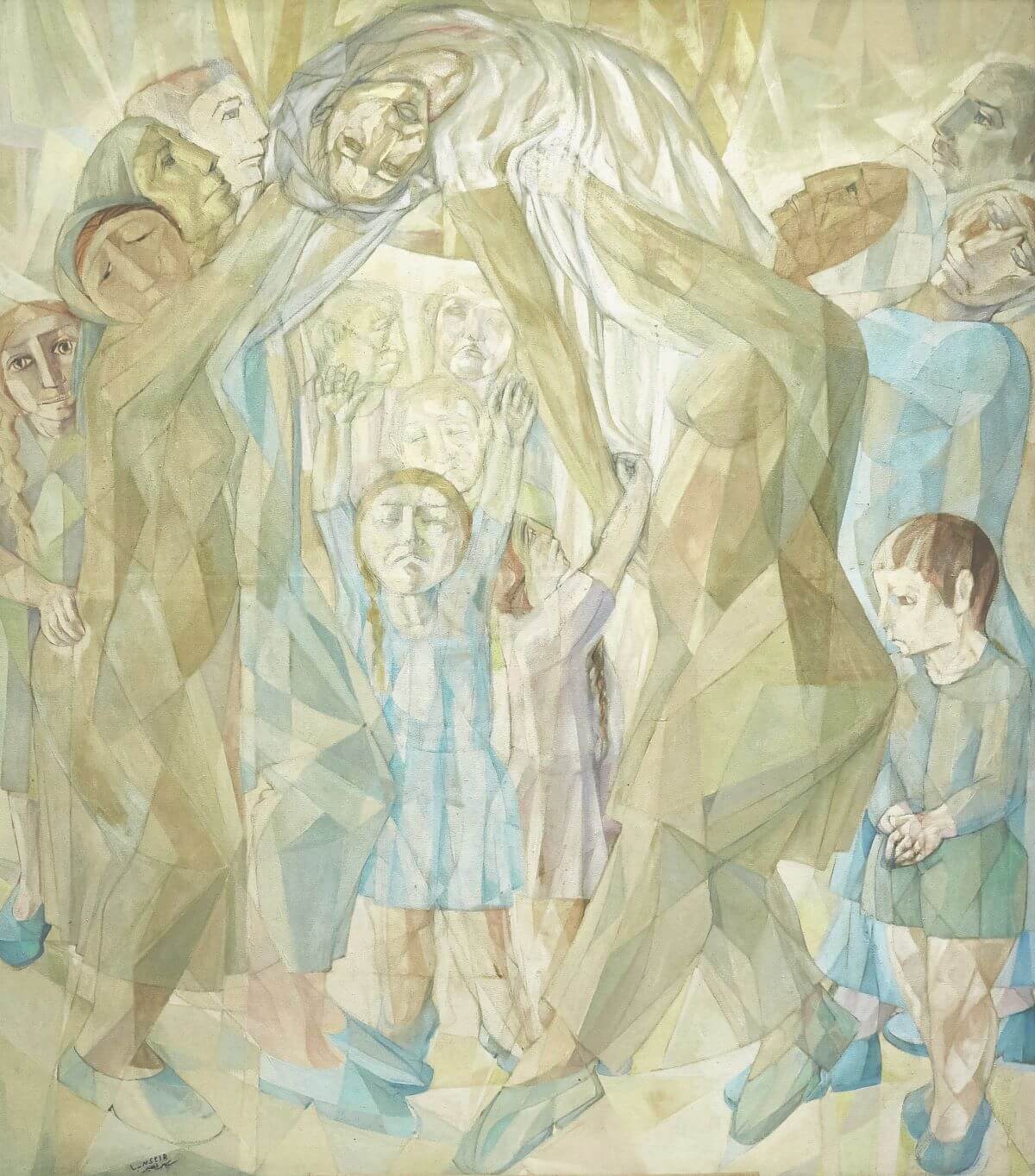

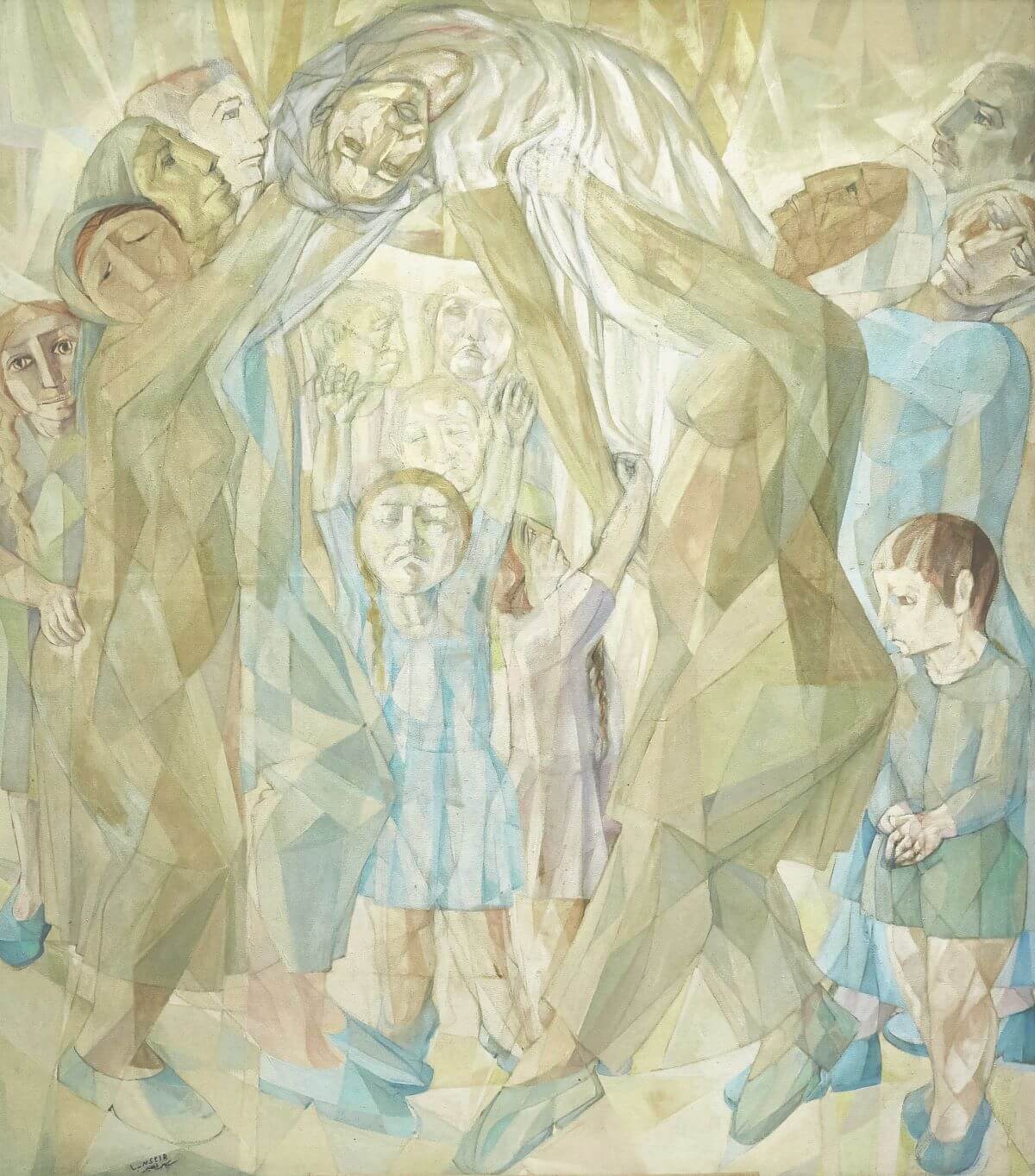

When you are asked, did Arab artists partake in Western art movements such as Dadaism, Pop or Fauvism, tell them our artists were part of great schools of art that were relevant to our history and context. Tell them about Aleppo-born Madiha Umar‘s 1940s Lettrism movement that emancipated the letter from the word and was adopted by artists throughout West Asia and North Africa. Tell them about Iraqi Shakir Hassan Al Said whose One Dimension aesthetic theory drew from Islamic spirituality. Tell them about Sudanese Kamala Ibrahim Ishaq‘s Crystalists Manifesto, Kuwaiti Khalifa Al Qattan‘s Circlism, Algerians Choukri Mesli, Baya Maieddine et al.’s Aouchem Manifesto that is inspired by millenia old rock art of the Tassili mountains. Tell them about the Moroccan Casablanca Group, the Egyptian Arts and Liberty Group which brought together Muslims, Christians and Jews, Saudi’s Mohammed Al Saleem‘s Horizonism, and the pivotal founding of the Baghdad Modern Art Group in 1951 that called on Iraqi artists to “reconnect the continuity” that was lost following the 13th century Yahya Al Wasiti‘s school of art.

If they ask you about diversity, tell them the Arab World included Jewish artists such as Egypt’s Ezekiel Baroukh, Morocco’s Andre El Baz, Palestine’s Jussuf Abbo and Tunisia’s Jacob Chemla not to mention the many non ethnic Arabs artists who are Amazigh, Armenian, Persian and Kurds. Speak to them about our pioneering women artists such as Palestine’s Zulfa Al Saadi (1905-1988) who exhibited her works at the First National Arab Exhibition in Jerusalem in 1933, or Lebanon’s Marie Hadad (1895-1973) who showed at the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair, or Egypt’s Amy Nimr (1898-1974) who debuted at the Paris Salon d’automne of 1925. When they ask you about solidarity, tell them Arab artists stood with Palestinians and Algerians in their struggle for freedom such as Dia Azzawi‘s seven and a half metre long Sabra and Shatila collage or the now missing Massacre of Algeria (1956) by Iraq’s Mahmoud Sabri. Tell them Arab artists stood with the Vietnamese, South Africans, Cubans and Congolese, just look up Kamal Boullata‘s posters and Ibrahim El Salahi‘s Funeral and the Crescent which honours Patrice Lumumba. When they ask you about love, speak to them about Etel Adnan and Simone Fattal‘s 50 year bond. Tell them about Saad El Khadem‘s paintings of his wife Effat Nagy, including ones in the nude that hangs in their joint museum in Cairo. Tell them about May Muzaffar and Lily Farhoud‘s dedication to the legacies of their late artist husbands Rafa Nasiri and Kamal Boullata along with English-born Lorna Selim who supervised the completion of her late husband Jewad Selim‘s Monument to Liberation in Baghdad after his sudden death in 1961. Tell them about Jumana El Husseini‘s love for her city of Jerusalem which she continued to paint seven decades after her exile.

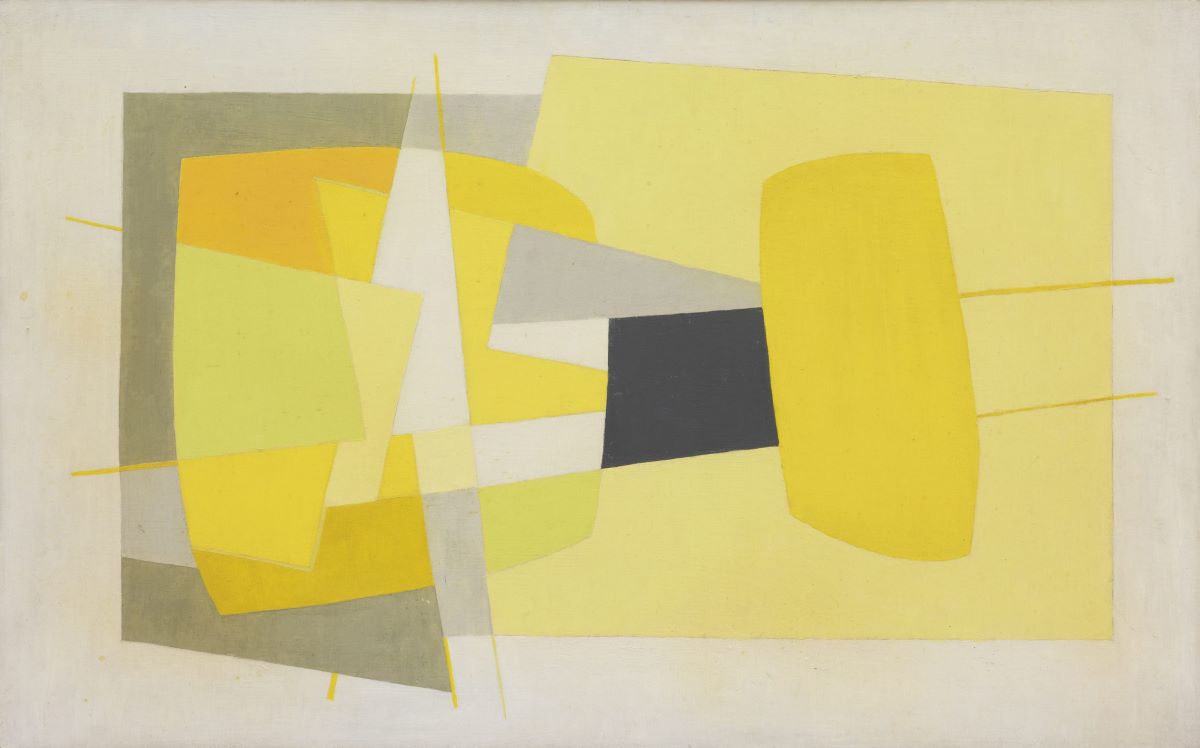

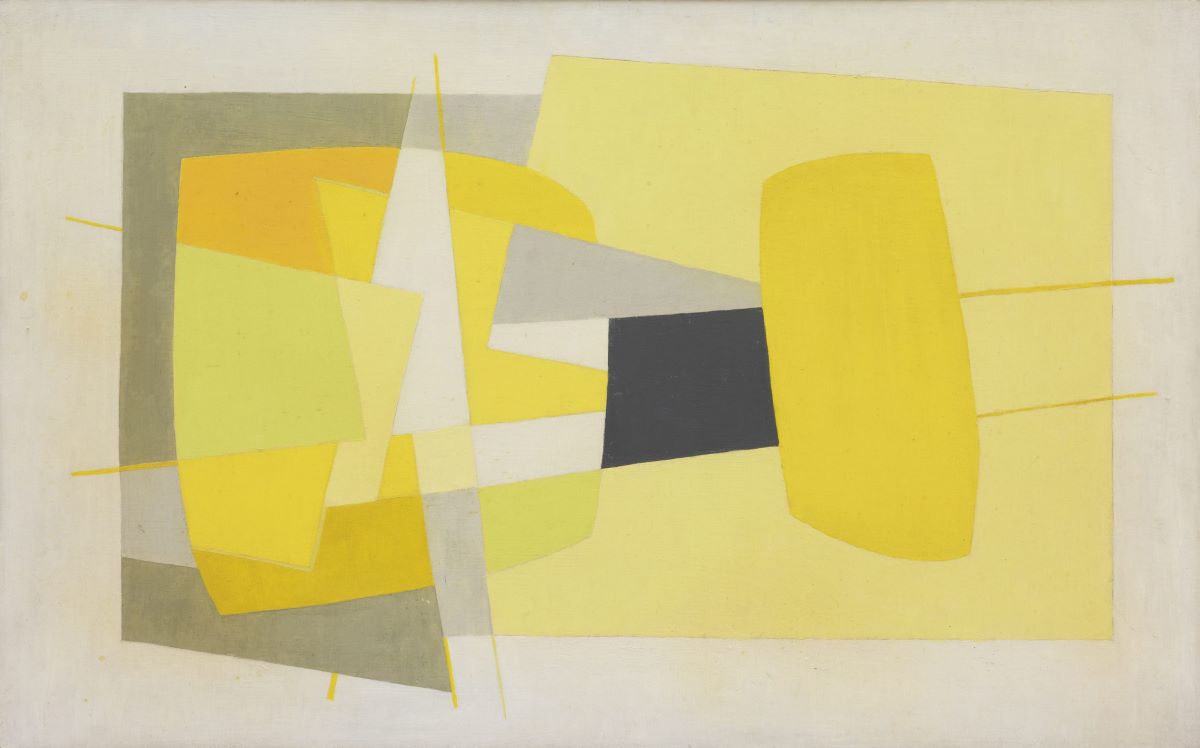

If they ask you about innovation, tell them about Nadia Saikali‘s 1970s colourful light installations that resemble a silhouette of a city, the UAE’s Hassan Sharif‘s 1980s conceptual performance art that saw him walk into the Hatta desert as though he is leaving civilisation behind, not to mention Egyptian Armenian Van Leo‘s dramatic surrealist photos of the 1940s in which he used novel techniques including solarization and multiple exposures. Tell them about Saloua Raouda Choucair – a Lebanese pioneer in abstract art, who is said to have held the very first abstract art exhibition in the Arab World in the 1940s, was also very much influenced by scientific and mathematical concepts, as well as by the laws of physics and mechanics.

Speak about modern Arab art with your friends, with your families and with non-Arabs. Arab art should matter to you because it is relevant to your context. It is about you. Arab art is about our history, our beliefs, our triumphs and our failures. It is about our emancipation movements, our unshakable spirits, our heroes, our lovers, our everyday man and woman. It is what makes us who we are. Do not let anyone tell you otherwise. Indeed it is important to know about Guernica, Cinqo do Mayo and The Garden of Earthly Delights. However, for us, I believe that it is even more important to know about Camel of Burdens (Jamal Al-Mahamel), The Last Sound and Baghdadiyat. The same goes for our friends in South Asia, Iran and Africa, all of whom have great works of art worthy of being widely acknowledged and recognised.

Do not let others compartmentalise you. Your art is part of a greater nation. Your art is the art of Egypt, the Maghreb, the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula. It is an art that reflects the beauty of our desserts, oases, mountains and valleys, an art that is of our historical sites and modern cities. It is an art that in addition to its cultural, political and social significance is above all aesthetically pleasing to the eye. It is the art of 400 million people and 8,000 square miles. Even experts really know only the tip of the iceberg.

Finally, speak up for Arab art. It is important that you demand it from your cities, from your states, from your countries in places where it can be seen. Western art is in no need of patronage. Arab art is, and Arab artists are. But without your voices it will continue to be relegated to a secondary status, an afterthought. Demand that your libraries stock books on Arab art, demand that your schools teach Arab art, demand that your popular culture, movies and advertisements feature Arab art. Again, this must be a concerted effort, governments and citizens alike, corporations and NGOs, mass media and social media influencers, if we were to secure our place in the world and if we want our identities to not be “defeated by oblivion” as Anton Shammas wrote. Do not be discouraged by those who do not know your culture or cannot appreciate its beauty. Educate yourselves about Arab art, take pride and share with others.