Initially, I planned a completely different piece for this month’s column, but as…

What is Islamic art? Historical perspectives and new debates

What is Islamic art? Historical perspectives and new debates

The commonly accepted definition for Islamic art refers to the artistic and architectural production made in regions that extend from Spain to India, between the 7th century until the 18th century – this area was the home to the various Islamic empires including the Umayyads, Abbasids, Seljuks, Mamluks, and Ottomans. It is worth noting that although this art was created in regions where Islam was a dominant cultural force, it was not necessarily religious art. This, consequently means that the term ‘Islamic’ art is not comparable to that of ‘Buddhist’ or ‘Christian’ art, which are generally based on faith. Contrastingly, Islamic art was created by Muslims and non-Muslims alike, although within the sphere of Islamic influence. This umbrella term includes several art forms such as architecture, decorative art, ceramic art, mosaic, relief sculptures, drawings, paintings, textile, calligraphy, and metalworking. Considering how widespread the various Islamic dynasties were and their influence geographically, historically, and culturally, Islamic art was subjected to a variety of regions, both in East and West. Thus, it evolved and developed through different periods, regions, styles, and influences.

The study and display of Islamic art in a historical sense originate from the West. The first collections of Islamic art were formed in Europe in the late 18th century, a practice that continued well into the 20th century on both sides of the Atlantic. When considering Islamic art and the discipline surrounding it, one should be mindful of its complicated relationship to Orientalism and Colonialism – two ideologies that greatly affected the birth of this discipline and the scholars’ approaches to it. Considering the larger artistic developments in the WANA region, one of the clearest manifestations of the harmful attitudes exhibited by Westerns was the open dismissal of ‘Islamic’ art as an art form. Consequently, the early modern artists of the region internalised the indigenous art production, for instance, Islamic art, as a non-art, believing that they came from a surrounding void of art.

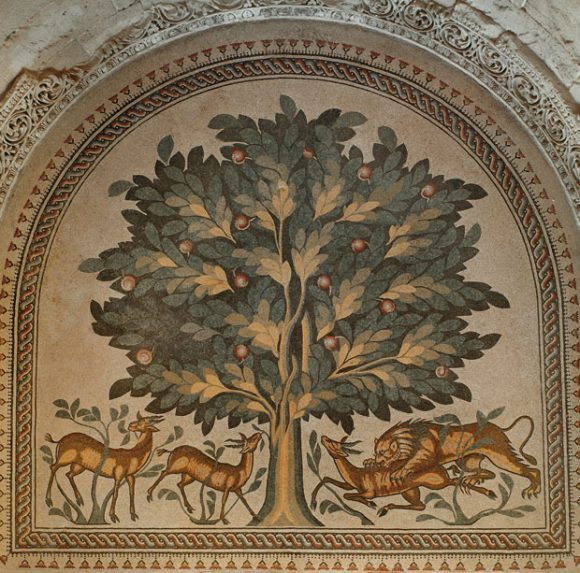

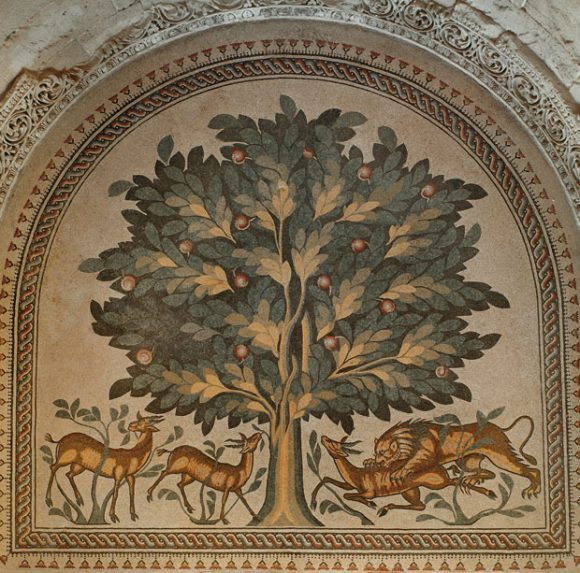

Considering the aforementioned definition of Islamic art and the vast extent it covers, it is impossible to go through all of its specificities within the context of this article. We may, however, look at some of the key features of this art form. In our existing understanding, the basic components of this artistic production encompass Islamic ornament in the form of calligraphy, vegetal motifs, geometric patterns, and figural representations. During the early phases of Islamic art, vegetal motifs were adopted as the initial style. Occupying an entire sphere, the vegetal motifs are usually accompanied by geometric patterns that frame the dense and colourful motifs. These vegetal motifs were drawn from the Byzantine culture and other Mediterranean traditions. Calligraphy was conceived in various styles and schools. Its core element is to juxtapose a textual expression through a coded aesthetic. Although calligraphy is extensively used in Islamic art, it evolved in its application for non-religious content. For instance, Arabic calligraphic expressions include poetry, proverbs, signages, and praises of rulers. Similarly, geometric patterns have developed as one of Islamic art’s unique visual languages, taken from Islamic sciences such as mathematics and astronomy. They are sometimes isolated as their respective designs, but they mainly accompany other types of ornamentations, such as vegetal motifs and calligraphy. Besides, figural representations appeared in ornamentation depicting animals, fantastic figures drawn from pre-Islamic mythology, and stylised humans with no particular great significance.

In recent years, as the scholarship on modern Arab art has developed further, the field of Islamic art has also partaken in a number of fascinating debates. Arguably, one of the most perplexing debates has been centred around the possible continuity of Islamic art. For a considerable time, there was a widespread understanding amongst the scholars of Islamic art that there is no connection between the contemporary art world and Islamic art. One of the first scholars to challenge this perception was Wijdan Ali, an art historian, practicing artist and the founder of the Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts, arguing that, contrastingly to the commonly accepted definition, there is, in fact, modern and contemporary Islamic art. This understanding became more accepted and perhaps ultimately also more well known through an exhibition the British Museum organised in 2006. Although the terms ‘modern’ or ‘contemporary’ Islamic art were not explicitly stated, the exhibition proposed a continuity between the historical and modern and contemporary forms of creation. The Word into Art exhibition curated by Venetia Porter led other scholars such as Linda Komaroff to rethink their understanding of the umbrella term ‘Islamic art’. Consequently, Komaroff, a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) started a collection of contemporary Middle Eastern art at the museum, praising Porter for widening her understanding of the term. Not everyone in the field agrees, however, with the concept of ‘modern’ or ‘contemporary’ Islamic art. One of the most vocal critics of these terms has been professor Silvia Naef, who considers them as examples of invented traditions, basing her argument on the introduction and development of modern art in the region. We will return to this debate later during the Holy Month as it such a lively and perplexing one – irrespective of the argument you agree with, surely we can all agree that this debate has certainly created new and novel interest towards the discipline of Islamic art – and that is something we can all be glad about.

Featured image: Umayyad period mosaic.