In Conversation: Ilyes Messaoudi

In Conversation: Ilyes Messaoudi

In this interview, Ilyes Messaoudi (b. 1990, Tunis) talks about his background, practice, and most recent projects. By integrating his artistic practice as a didactic tool, he aims to bring awareness to forgotten histories and celebrate important figures in North Africa. In addition to being an artist, Messaoudi is also the co-founder of Galerie La La Lande with Sofien Trabelsi in Paris, supporting many artists hailing from West Asia and North Africa. His most recent solo exhibition Kahina is held at Foreign Agent Gallery in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Wadha Al-Aqeedi: Could you please introduce yourself and tell us about your path to become an artist?

Ilyes Messaoudi: My name is Ilyes Messaoudi, and I am 31 years old. From the age of 14, I practiced art by experimenting with many mediums, such as silk, wood, glass, and canvas. I never showed my work because it was very personal to me. I went on to pursue my studies in design at the Design School in Tunis. Soon enough, I discovered that I didn’t really want to continue in this path and have a career in design. I felt that painting was more fitting and freeing for me than design. At the beginning, I was very inspired by l’Ecole de Tunis–a historic art movement in Tunisia. I introduced some pop culture elements in my work, to give a contemporary version.

After graduating, I moved to France to start my career and establish myself as an artist. I have been living in France now for seven years. I started my artistic career with my ongoing project titled 1001 Nights of Scheherazade. With a contemporary take on the story, I look at Scheherazade as a feminist and a modern woman figure who rebelled against society. I am working on the series to achieve 1001 small canvases in which the heroine is confronted by situations, and she rises to the occasion and rebels. Each canvas recounts a short story from the collection of tales. Thus far, I have made 138 works. My last 3 paintings are actually NFT works. I primarily work on the strong female figures in the Arab world. Recently, I explored the tale of the Kahina which I discovered as a child. I have a special connection to Kahina because she is Berber. In fact, my grandmother is Berber and has tattoos. This connection pushed me to work on the Kahina story.

WA: How did you start the Kahina project?

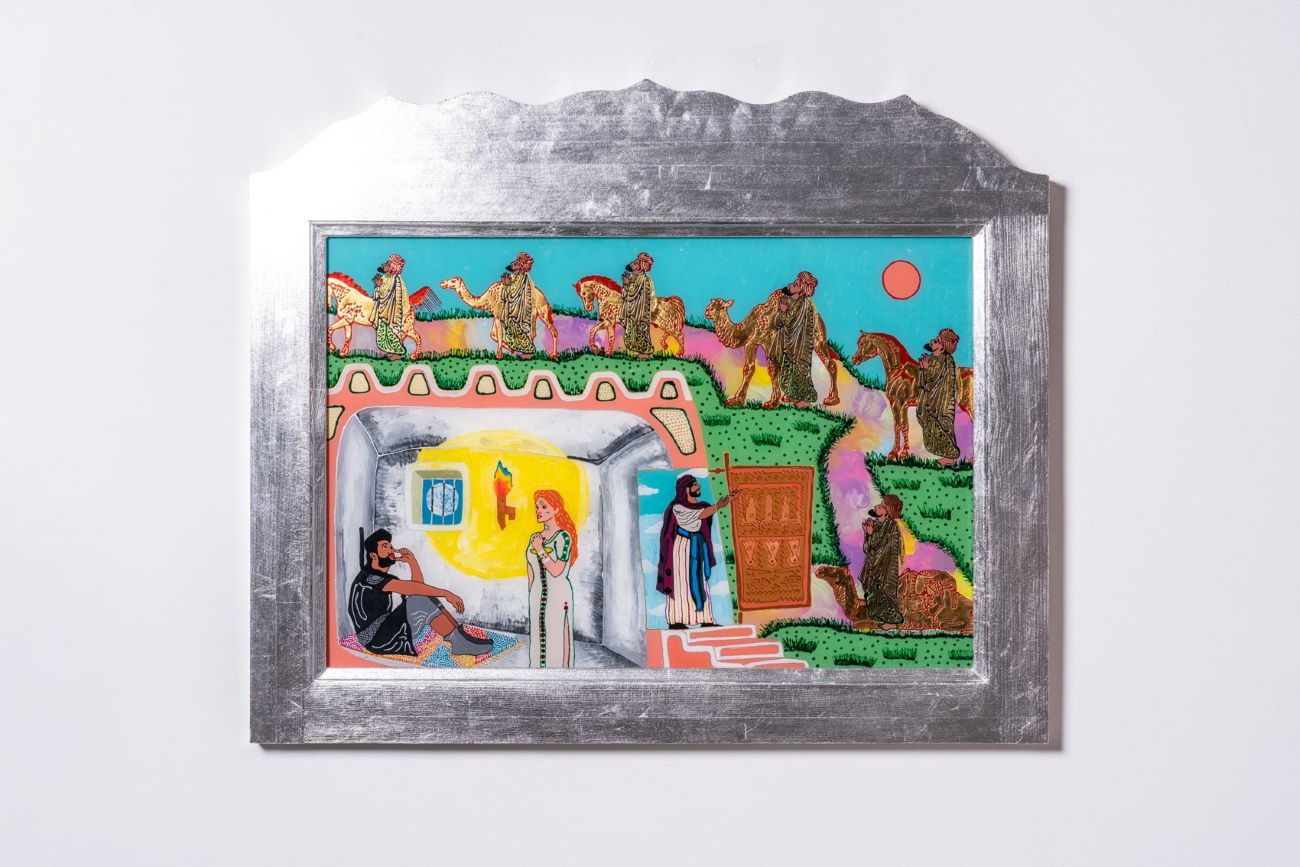

IM: So, author, curator and essayist Aurélien Simon wrote a book about the life of Kahina, her battles, and resistance against the Umayyads in North Africa. I contributed to the project by illustrating the book, which will come out in February 5, 2022. As a result of the book collaboration, in which I made 12 illustrations to accompany the 12 chapters, I created 12 works on reversed glasses combined with textile made of a traditional Berber technique rich in motifs and colours. Combining both techniques, I also framed the work with a traditional wooden frame specific to Tunisian craftsmanship. To expand on my interest in the Kahina as a historical figure, I created 12 illustrations with a specific technique of painting; reverse oil painting on glass, which is painting under glass.

Building on the Kahina herself, she is a Berber queen and an avant-gardist feminist from the 7th century. She fought against the Umayyads to oppose their invasion of the mountainous region of Aurès–a territory which lies today between Algeria and Tunisia.

WA: In your work, you tend to juxtapose the Orient, Occident, tradition, and modernity–How did you arrive at that focus?

IM: I think that history repeats itself, back and forth, between what is progressive and regressive. So, in my work, I try to change mentalities somehow because in the Arab world we are really attached to religion and retrograde traditions and values that shape our identity. Thus, I try to challenge these notions of identity in order to progress towards freedom. My work also looks back on history, specifically at how women were more liberated, and our communities were less patriarchal. Indeed, patriarchy imposed how a woman should be, caused inequality, and normalised violence against women. My work draws on these very current issues, with an aim to change the society’s mindset.

WA: We could assume that the woman figure is central to the utmost in your work. Going back to your most recent project, could you elaborate on the significance of Kahina to you and modern-day Tunisians?

IM: To me personally, the Kahina represents my grandmother, my roots, my culture, Tunisia, and North Africa as a whole. She is the Kahina that North Africans are all proud of. Presently, this historical figure is being erased from our collective memory and folktales. She surely remains as part of our history, but we need to celebrate and remember her more. For instance, young children in school are not learning about her. That is why the Kahina book project came into being, targeting both children and adults.

WA: What a seminal project! Could you tell us more about how you collaborated with Aurélien Simon to bring this project to life?

IM: I met with the author Aurélien Simon to discuss the project. He visited Tunisia three times and was interested in Décor Star Wars Tunisie. During his exploration of the Tunisian history and culture, he came across the story of Kahina. As a result, we talked about it, he authored the book, and I illustrated the images accompanying the texts. We are currently working with three Publishing Houses in France, Tunisia, and Algeria.

WA: Besides being an artist, you are also a gallerist. Could you tell us about Galerie La La Lande in Paris, and how do you balance your roles as an artist and a gallerist?

IM: I started as an artist, and I was lucky to have many collectors acquire my work. After meeting Sofien Trabelsi, who is my partner in the project, we founded the gallery together in 2018. We started to represent artists from the MENA region, especially from North Africa. I injected the collectors of my work and my clients into the gallery. Then, we were fortunate enough to meet a lot of people who supported, believed, and encouraged us. After exhibiting at L’institut du monde arabe, we found a large space close to Centre Pompidou. We were able to support more artists, exhibit and integrate their work in private and public collections, and participate in art fairs. Currently, many of our artists have upcoming exhibitions in reputed institutions; Slimen Elkamel at L’institut du monde arabe, and Aïcha Snoussi at Palais de Tokyo. So, I think the fruits of our labour are paying off.

WA: Lastly, what is the driving force behind your important work as an artist?

IM: I think my art is didactic, i.e., educative. So, I hope that the book will bring awareness to the neglected historical figures from our culture and history. I hope that the Kahina book reaches the masses in North Africa, especially children. All in all, I would like to think of my work as didactic.

In Conversation: Ilyes Messaoudi

In Conversation: Ilyes Messaoudi